Unposted, On Purpose

On private beauty and the refusal to perform, against the flattening of experience

Some things only bloom in the absence of an audience.

I keep returning to that line although it doesn’t sound wise, it actually sounds faintly like something stitched on a linen cushion, but it has proved stubbornly, annoyingly true. The moments that stayed with me this winter, the ones that lodged themselves somewhere behind the ribs and refused to be filed away, were precisely the ones that never crossed a screen. They survived because they weren’t translated. They didn’t have to become legible.

January did something strange to me. Or perhaps I finally did something strange to January. I travelled. I saw friends. I went to concerts, theatre and opera. I laughed hard enough that my body registered it before my mind did. I ate incredible food. I wildly made love. I walked cities without narrating them. And somewhere between one airport lounge and a train station, I entered what I half-jokingly call social media hibernation. I didn’t announce it. I didn’t detox. I didn’t post a farewell story explaining my “intentional break.” I simply… slowed down, and then stopped.

No documentation. No careful framing of joy so it could pass inspection.

At first, this felt irresponsible. Almost antisocial. As if I were withholding something owed. That reflex alone should worry us more than it does.

We live inside a culture that treats experience as provisional until proven by witnesses. If it wasn’t shared, was it real? If it wasn’t captured, was it felt deeply enough? We have internalised the idea that memory requires a server. That intimacy needs a feed. That beauty, unless externally validated, risks evaporating. The pressure isn’t always loud. Often it’s polite. A gentle itch. A sense that you’re behind if you’re not seen.

I felt that itch too. Sitting across from someone I love, mid-conversation, a sudden impulse to freeze the moment, not by staying in it, but by extracting it. To turn warmth into evidence. I hated that impulse. I also recognised it… which is worse!

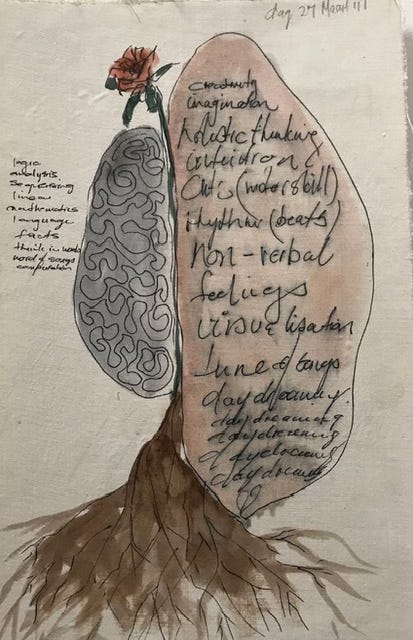

Because the problem isn’t social media per se. The problem is what it trains us to do with our attention. To siphon lived moments into a secondary economy where they can circulate, be appraised, be responded to. Even grief now feels faintly incomplete without a caption. Love, unless periodically signalled, risks being misunderstood as neglect. Art, unless packaged for visibility, is treated as hobby or failure. This is not neutral; it shapes the nervous system, and it rewards exhibition over digestion.

And before this turns into a sermon from someone who has absolutely participated, yes, I have posted sunsets and moons and plates and faces and paintings and sentences I believed in, let me say this clearly: I am not advocating silence as virtue. I write publicly. I believe in words that travel. I believe in shared language. I also believe, increasingly, that some things rot when exposed too early. Or too often. Or at all.

There is a difference between expression and extraction. The first comes from necessity. The second from habit. We have collapsed the distinction.

There is an old religious intuition, older than any platform, that the sacred requires concealment. That revelation without preparation becomes noise. Think of the Eleusinian Mysteries, the taboo around naming God, the structure of initiation rites where knowledge is earned slowly, through disorientation, repetition, discomfort. You were not meant to see everything. And certainly not all at once.

Now contrast that with the current demand to narrate in real time. To flatten duration. To offer your interior life as a running commentary. We have traded mystery for metrics and then wonder why everything feels thinner.

During my January absence, something unexpected happened: my experiences grew heavier. Not oppressive! But denser. They gathered weight the way good objects do when you stop passing them hand to hand. A conversation lasted longer because it wasn’t compressed into a takeaway. A shared silence remained intact because it wasn’t turned into a caption. I watched light slide across familiar and unfamiliar streets, ate meals that didn’t need proof, laughed with friends in places beautiful enough to beg for documentation, and chose not to lift my phone. At a concert, surrounded by glowing screens held up like offerings, I kept my hands empty and let the music exist without proof. Nothing was lost. On the contrary: the moments stayed textured, unedited, astonishing, mine! The absence of an audience didn’t diminish them. It sealed them.

No one knew. Which meant all those moments were really mine.

There is a particular violence in being forced to perform coherence too soon. Grief understands this. Real grief doesn’t want an update. It wants privacy, time, incoherence. The minute grief becomes content, something to be contextualised or made relatable, it loses its right to be what it is: a rupture.

Love, too, suffers under constant exposure. The most intimate bonds I know are not the most visible ones. They don’t need to be defended or displayed. They operate off-screen, where trust isn’t confused with transparency.

We pretend this is new. It isn’t. What’s new is the scale. And the speed. And the way platforms subtly moralise visibility. To be seen is to be generous. To share is to be open. To withhold is to be suspect. “Why didn’t you post?” is now a question that carries accusation. What are you hiding? Who are you without witnesses?

But privacy is not secrecy. And restraint is not fear. Sometimes it is discernment.

I’m wary of essays that argue too cleanly against “the digital age” as if one could simply opt out and return to candlelight and handwritten letters. That fantasy ignores how embedded these systems are, not only economically, but psychologically. We are shaped by them. I am shaped by them. The rupture is not between “online” and “offline”. It’s between what is metabolised and what is prematurely exported.

But what if the problem isn’t sharing, but timing?

What if some experiences need to sit inside the body, unarticulated, before they are asked to mean anything at all?

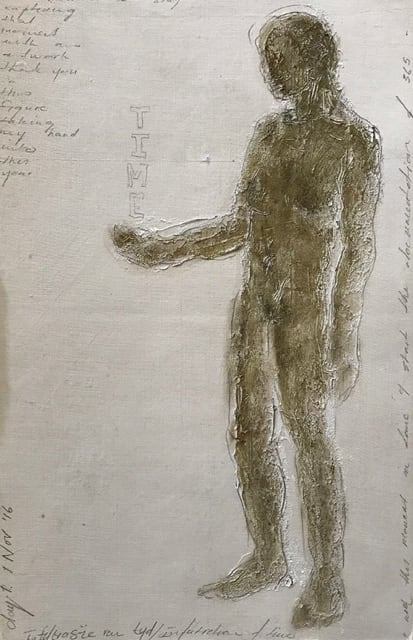

Art has always known this. The sketch stays in the drawer. The draft is unreadable. The painting turns toward the wall… it isn’t necessarily precious, but it is unfinished. Yet we now ask people to publish their sketches as statements, their drafts as declarations. We reward immediacy and punish hesitation. We call it authenticity. Often it’s just impatience.

I felt that impatience in the beginning, when I didn’t post. So many beautiful things I saw and experienced without sharing them. A strange anxiety, like missing a roll call. As if the world were continuing without my proof of presence. Which, of course, it was. That’s the point!

Humour helps because otherwise the critique becomes unbearable. There is something faintly ridiculous about adults carefully staging spontaneity. About the choreography of “casual” joy. About the influencer trope of crying attractively into a ring light. Intimacy is then dead. It becomes theatre with better lighting. We all know it. We all participate anyway.

And then there are the moments that resist staging entirely. The ones that refuse to sit still in order to be framed. A look exchange that carries history. A silence that says more than explanation. The body learning something the mind will only understand later. These moments don’t photograph well. Of course they don’t. They don’t scale. They don’t convert. Which may be their greatest virtue.

I remember a dinner in January. Late. Too much champagne. A table of friends who know my worst and still pass the bread. Someone said something unguarded. The room shifted. We stayed there. No phones. No records. If I tried to describe it now, it would sound trivial. It wasn’t. It was decisive and recalibrated something in me. That recalibration did not require witnesses.

This is where the argument becomes uncomfortable, because it asks us to relinquish something we’ve been trained to crave: recognition. Not praise! Just recognition, the sense that one’s interior life has been acknowledged, mirrored, validated. Platforms exploit this need brilliantly. They don’t create it. They amplify it. And in doing so, they silently suggest that unrecognised experience is lesser experience.

I don’t believe that. In fact, I think the opposite may be true. The moments that shape us the most profoundly often bypass recognition altogether. They rewire without applause. They leave no trace except a subtle change in posture, or choice, or tolerance for bullshit.

There is a line, misattributed endlessly, but still useful, about living a life that looks good from the inside. I used to find it smug. Now I find it practical. A life organised primarily for internal coherence will often look odd from the outside. Unimpressive. Under-documented. And that’s fine.

This is not an argument for purity. I distrust purity. It curdles into performance faster than anything. I see it as an argument for selective opacity, for the right to let some things be half-formed, unshareable, or simply not for public use.

January didn’t only change how I moved through cities and rooms; it changed how I wrote here. I slowed down on Substack too, exceptionally. I didn’t keep my usual rhythm of two essays a week because I needed the same interval I was defending elsewhere. Some people unsubscribed. That happens when you refuse consistency as performance. I didn’t chase them back with explanations or filler. Writing, like living, needs periods of fermentation, not just output. If you’re here, it’s probably because you recognise that rhythm, that what’s offered less frequently, but with more interior necessity, tends to last longer once it lands.

When everything becomes content, experience loses its afterlife. There is no residue. No echo. No time for meaning to ferment. You move on too quickly, because the platform requires novelty, not depth. The feed forgets. So do you.

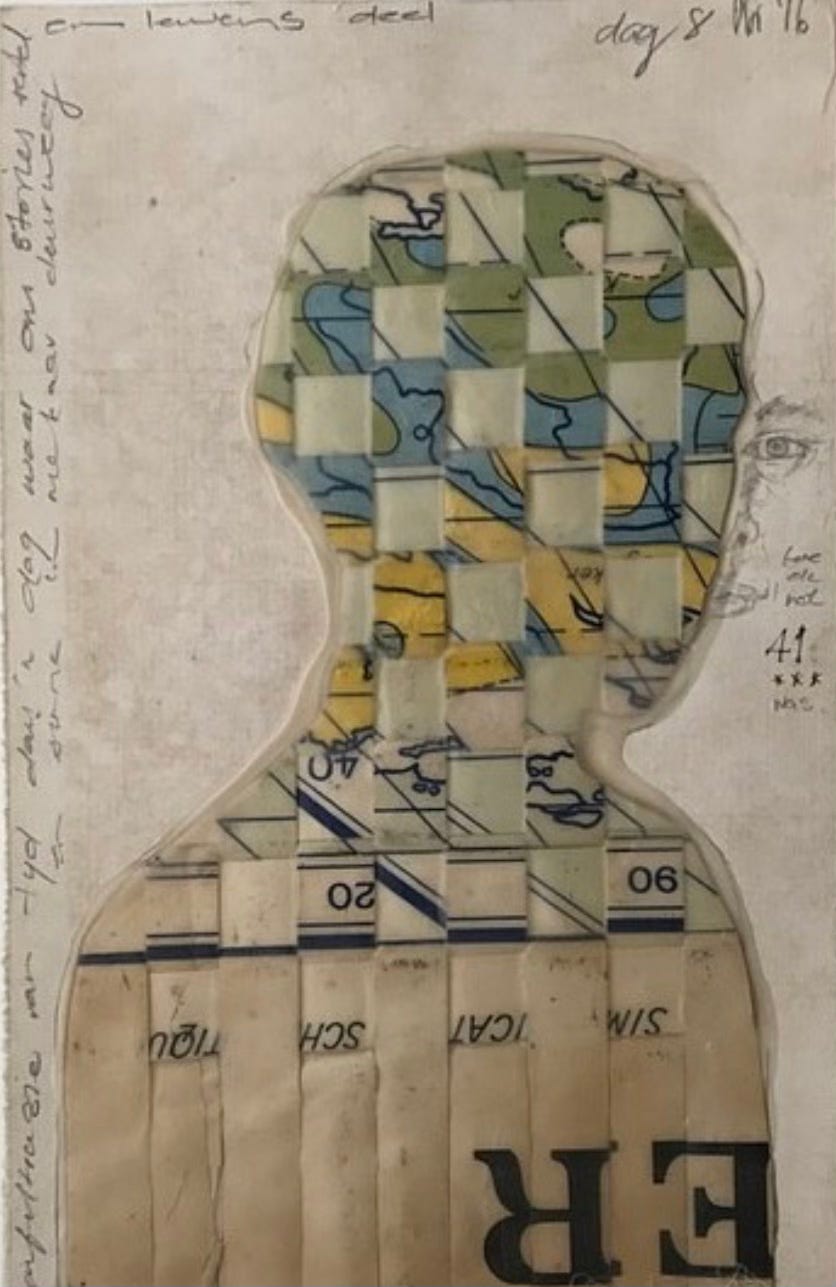

We’ve made a category error. We think documentation equals experience, that memory needs receipts. But some things calcify the moment you try to fix them. You take the photo and the moment becomes the photo, and the photo is always thinner than what it replaced, a pressed flower when you wanted the scent.

Roland Barthes got at this in Camera Lucida, though he didn’t have to contend with Stories. He wrote about how photographs wound us, how they are simultaneously proof that something happened and proof that it’s gone. Now we’ve weaponised that wound. We create it preemptively. We’re so busy producing the artifact that we skip the event itself, or worse, we perform the event for the artifact’s sake, which is a kind of existential hollowing-out I don’t think we’ve fully reckoned with yet.

Look, I’m not interested in some Luddite jeremiad about the death of presence. The internet gave me friends across continents and access to thinking I’d never have encountered. I know what the network makes possible. But I also know what it costs, and the cost isn’t something we can easily subtract from the balance sheet because it’s not quantifiable. It’s qualitative. It’s the texture of experience.

When every moment is potentially content, you start living for the edit. You don’t ask “What do I want?” but “What will this look like?” Your life becomes a rough draft of someone else’s life, someone you always try to become by proving you already are. The performed self eats the actual self. What’s left is a husk that photographs well.

In a small coastal town, a lot of wind, famous for almost nothing, I spent two hours watching fishermen repair nets. Just sitting there, doing nothing, contributing nothing. No one knew I was doing this. I didn’t tell anyone about it until right now, and I’m only telling you because it’s illustrative, not because it matters. The point is that it happened in a pocket outside the attention economy. No value was extracted. No engagement was generated. It was just time passing at the speed it actually passes when you’re not trying to package it.

Indeed, some things only bloom in the absence of an audience. And I don’t see it as a metaphor. There are night-blooming flowers – cereus, anyone? – that open for exactly one evening and if you try to photograph them with a flash, they close. The conditions for their beauty are darkness, privacy, the absence of the gaze. Introduce surveillance and you kill the phenomenon you came to witness.

We know this about sex. We know this about prayer if you pray. We know this about the first time you cry in front of someone, or the moment you realise your father is mortal, or any of the other threshold experiences that require a kind of rawness that can’t survive exposure. But we’ve been persuaded by platforms, by peer pressure, by the sheer momentum of late capitalism’s demand that everything be leveraged, that privacy is somehow suspicious. That if you don’t share, you withhold. That unposted experience is wasted experience, like a tree falling in an empty forest.

This is insane. This is deranged if you sit with it for more than thirty seconds.

But we don’t think about it because we’re too busy doing it. The reflex is faster than thought. Something happens and your hand moves toward your phone before you’ve consciously registered what you’ve seen. The documentation precedes the experience. You’re living in post-production.

Treating every moment as raw material for content, as something that only matters insofar as it can be leveraged for attention is grotesque. Never letting anything just happen without asking what it’s worth, what it signals, how it’ll be received is pathetic. The total entrepreneurialisation of selfhood, where you always hustle your own life like it’s a product in beta and the metrics are never quite good enough and you can’t stop iterating because stopping would mean disappearing is the lame norm today.

I think this is why everyone’s so tired. We perform ourselves into exhaustion without ever quite arriving at anything. The self becomes a project without an endpoint, a startup that can never exit, and all the KPIs are public and everyone’s watching and you’ve forgotten what you even wanted before you started wanting to be seen wanting it.

Joan Didion kept notebooks. Private ones. She wrote about the self who wrote the entries as though that person were someone else, a stranger she used to know. But at least she had the privacy of that estrangement. At least the notebook wasn’t calibrated for virality. Now the notebook is public and the audience is infinite and we’re all performing our innermost thoughts in real-time for people who’ll forget us by tomorrow, and I genuinely don’t know what this does to interiority over time. I suspect it empties it out.

I still look on Instagram and even here on Substack, and everything looks like an ad for itself. Everyone is selling a version of living that nobody actually wants but that we’ve all agreed to pretend was desirable because the alternative, admitting that most of life is boring and difficult and doesn’t photograph well, was too destabilising to the whole edifice we’d built. So we keep posting. We keep performing. We keep extracting value from our own experiences until there’s nothing left but the husk.

I think we should let some things die with us. No secrecy or shame, but some forms of beauty require privacy to exist at all. Because intimacy can’t survive constant exposure. Because the self needs a place to be incoherent, unfinished, not-yet-legible even to itself, and if every thought immediately gets threaded and every feeling immediately gets posted then where does the self retreat to in order to become something other than what it already is?

The moments I didn’t post in January are the ones I actually remember. The ones that changed something in me. And I can’t prove that to you, which is the whole point.

And yes, I will come back. I always do. Slowly. This is not a manifesto for disappearance. It’s a plea for intervals. For blank spaces. For the right to experience without immediately converting that experience into something legible.

There is a sensual dimension to this that rarely gets named. Sensuality requires privacy. Not secrecy, again, but containment. Desire thins under scrutiny; it performs, but it does not deepen. Anyone who has loved knows this. The more something is watched, the more it stiffens. The most erotic moments are not the most visible ones. They happen in half-light. In trust. In not being interrupted by the need to explain.

We have confused exposure with courage. Sometimes courage looks like restraint. Sometimes it looks like saying: this is not for you. Not yet. Maybe not ever.

That stance will not be rewarded by algorithms. It may cost you relevance. It may feel lonely at first. But it may also restore a sense of scale. A sense that not everything needs to be fed into the same machine.

There were moments when the reflex surfaced almost automatically: I should share this. People would like it.The thought arrived pre-digested, already calibrated to an imagined audience, already fluent in the grammar of approval. And then, a second thought, quieter, less efficient, followed behind it: maybe that’s precisely why I shouldn’t. Not out of contrarian virtue, but out of suspicion. Liking is never innocent. It is a social signal, a form of circulation, a small transaction of symbolic capital. Bourdieu would have recognised the move immediately: taste announcing itself, experience laundering itself into distinction, intimacy converting into a subtle form of status. What unsettled me was not the desire to be seen, which is human, but how quickly the moment began to reorganise itself around legibility. The experience was still warm, still forming, and already it was asking to be positioned. In those seconds, something delicate was at stake: whether the moment would remain lived, or be rerouted into display. Choosing not to share felt less like restraint and more like protection of the experience itself, but also of me, against the reflex to turn every pleasure into proof.

No superiority here! Only containment. Psychological withholding. Cultural discernment. A refusal to let every meaningful thing be flattened into the same format, the same tempo, the same scroll.

I don’t know how this ends. I don’t trust essays that pretend to. What I know is that some of the most alive parts of me right now are the least visible ones. That feels like a risk. It also feels like relief.

Not everything deserves a post. Not everything deserves photographic evidence.

Some things deserve silence. Some deserve time. Some others deserve dim privacy. Some deserve to be remembered imperfectly, by one person, with no proof.

That doesn’t save the world, it doesn’t dismantle anything, it doesn’t make you pure. But it might keep something human intact.

And that, lately, feels like enough to carefully, inconsistently hold onto, without witnesses, while the rest of us scroll past.

In private, unposted, on purpose,

Tamara

What’s sharp here is not the refusal to post, but the refusal to prematurely capitalise experience. You’re not arguing for disappearance. You have just diagnosed a sequencing error. Experience now enters circulation before it’s internalized, and what gets lost is the pressure that allows something to thicken into meaning. That’s a real intervention, and it lands because you inhabit it without moralizing it.

Platforms misprice experience. They reward legibility over latency. Anything that requires incubation, ambiguity, or failure reads as low-value in a system optimized for instant return.

But some forms of value only appear after prolonged non-visibility. Think of Cézanne, endlessly repainting Mont Sainte-Victoire, canvases turned to the wall, works considered failures or exercises for years. Those unexhibited repetitions are precisely what allowed modern painting to recalibrate how seeing works. If Cézanne had been required to “ship” each attempt, to justify each canvas as content, the very thing art history later named as value would never have survived the process.

That’s what makes your stance pragmatic rather than romantic. You point out that overexposure is not neutral to production. It changes what can be made. The culture of constant signalling produces not only thinner lives, but thinner work, people who subscribe to value early, cling to relevance metrics, and then wonder why so much of what circulates feels like flop dressed up as confidence.

We’re drowning in visible output precisely because so little of it has been allowed to fail privately first.

And the clarity of your decision matters. There’s authority in your presence because you don’t posture it as purity or exile. You model discernment. You show that withholding can be a form of care for the work, for the body, for attention itself. In a landscape obsessed with proving aliveness, you’re insisting on staying alive long enough for something to actually form. Honestly, it’s one of the few sane responses left. Brava, Tamara, as always.

The demand for performance, disguised as wellness checks and concern, are a product of the ephemeral and holographic nature of the online space. We act as avatars connected to other avatars, and in turn need proof of life at the same time and on the same channel, to compensate for the lack of genuine connection. In turn, the need for recognition creates the often guilt-ridden drive to perform and to reveal. And where it isn't guilt driving the compulsion, it's a fear of irrelevance; where absence turns to invisibility.

I love the point of internal coherence. The external world is, by definition, chaos, not because there isn't causal order, but because our minds aren't equipped to track the variables. The world doesn't become easier to navigate by controlling the external, but through internal coherence, guiding the person from the inside out. Your January excursions were a crucial act in the practice of this internal coherence. You experienced without documenting, fortifying your inner world by keeping those moments and memories sacred and undistilled. In the same way that we've lost the capacity to remember phone numbers and birthdays because our phones and social media do that for us, to perform an experience expels it; the experience becomes the document, thrown into the causal soup of the external, leaving a gap in the internal archive. The experience is no longer the experience, but the Instagram story or essay you wrote, which becomes redefined and even tainted by its exposure to the outside.

Ironically, it's the time away that makes you more present, because of those experiences that fortify your internal coherence. And those who really love you - those who themselves are fortified, not by your presence alone but by the knowledge that you are nourishing yourself - will be as glad that you took the time away as they are that you've returned.

Beautiful, Tamara. Welcome back.