The Year Ends Before We’re Ready

Unfinished lives, deferred desires, and December’s silent interrogation

December doesn’t end the year. It interrogates it.

It happens earlier than we admit.

Not on December 31st, not at midnight, not when champagne foams performatively over flutes and someone insists, too loudly, that this is our year. No! The year ends sometime in early December, often on a Tuesday, while you are doing something insulting in its ordinariness: standing in line, deleting emails you never answered, realising that a promise you made to yourself has discreetly expired without protest. The year ends silently, without ceremony, and leaves behind a question that does not sound like a question at all but behaves like one.

Is this it?

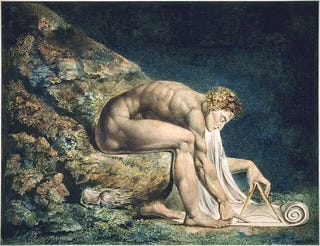

December, contrary to its aggressive branding, is not festive but forensic, arriving with the air of a mid-level auditor and a clipboard, rifling through your mental files with the weary competence of someone who has heard every excuse already, unimpressed by your good intentions, unmoved by the emotional footnotes, and deeply uninterested in your precious “process”, unless it accidentally produced something verifiable: an outcome, a decision, or at the very least a clean, unembellished confession.

You feel it as a low-grade agitation. A tightening. A peculiar restlessness that is not quite regret and not quite ambition, but some irritating hybrid that keeps you awake at night while being useless during the day. People call it end-of-year reflection to make it sound like a spa treatment. It isn’t. It’s an audit. And like most audits, it uncovers discrepancies you were perfectly happy not to notice.

The panic begins before the year ends because time, in December, stops behaving like a neutral container and starts acting like an interrogator who already knows the answers.

Everyone is secretly auditing their life right now. Some loudly, through posts and lists and resolutions that read like corporate mission statements for the self. Others privately, with a glass of something strong and the sinking sense that too much has been deferred under the illusion of “later”. Later, that generous fantasy. Later, the soft lie we tell ourselves to keep functioning.

Later does not survive December.

What makes this moment especially cruel is that it arrives just as the culture insists on cheerfulness. You are expected to sparkle while your inner ledger bleeds red ink. There are lights everywhere, and yet the dominant emotional register is not joy but unease, the sense of being behind on a syllabus no one remembers enrolling in. You are meant to celebrate time passing at the exact moment you become most aware of how little of it you have actually inhabited.

This is not New Year anxiety. That comes later and has a different texture, more performative, more aspirational, more easily medicated with slogans. What I am talking about here is pre-New Year anxiety, which is quieter, sharper, and harder to outsource. It’s the anxiety of unfinished business, unlived selves, unresolved desires that did not politely expire just because you were busy.

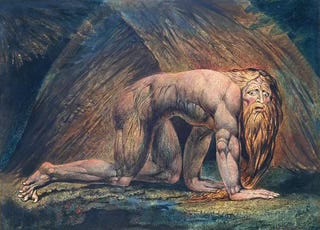

Time, once December sets in, commits a particular kind of violence that has nothing to do with spectacle and everything to do with pressure, a psychological constriction rather than anything that would register as dramatic, because there are no explosions to look at, no events to point to, only a steady closing in, a tightening that creeps up on you as everything you had spread out across the year gets pulled back, folded up, and packed in on itself. What once felt expansive starts to cave inward; days shrink, margins narrow, and the year, having run out of patience, curls itself into a tight, faintly hostile question mark and leans it straight into your chest, not to knock you over, but to see how much weight you’re willing, or able, to carry without stepping away.

What did you avoid? What did you almost do? Who did you nearly become?

These are not philosophical questions. They are tactile. They show up in the body. In the shoulders. In the jaw. In the way you scroll with increasing aggression, as if content might absolve you. It doesn’t.

I am not immune to this, although for years I liked to think I was, having convinced myself, on the back of enough introspection to pass for wisdom, that I was too reflective, too self-aware, too thoroughly “worked through” to be caught off guard by December’s little ambushes, as if insight were a kind of vaccination and I had already had the shot. That assumption, it turns out, was pure arrogance. December always finds a way in; it slips through the cracks you forgot were there, pokes at the joints you stopped testing, and this year it didn’t arrive with anything grand or operatic but crept up through something almost laughably small and faintly humiliating: a note I had written to myself in January, earnest, ambitious, maddeningly precise, now turning up again months later like an abandoned pet that somehow made its way back home, thinner, and clearly unimpressed by all the reasons you had for leaving it behind.

I had meant it at the time. That’s the worst part.

Realising that your past self was sincere, and that sincerity still wasn’t enough is uniquely destabilising. It dismantles the comforting narrative that failure only happens when we don’t try. Sometimes you try. Sometimes you try intelligently. Sometimes you even try bravely. And still, the year ends before you are ready.

We like to imagine time as linear because it flatters our sense of control. Progress narratives depend on it. So does self-help. So does productivity culture, which thrives on the fantasy that if you just structure yourself correctly, time will cooperate. December exposes this as wishful thinking. Time is not a line. It is a pressure system. And in December, the pressure drops suddenly, making everything feel heavier, more urgent, strangely volatile.

This is why people panic-buy meaning in late December, scooping it up wherever it’s displayed with enough confidence: retreats booked on the vague promise of “reset”, courses that swear they will integrate what the year failed to teach, planners heavy with aspirational blankness, end-of-year rituals borrowed from traditions we don’t belong to but hope might still work if performed sincerely enough. There are ceremonies involving candles, baths, lists burned or buried or ceremoniously folded, apps that generate your “year in review”, podcasts offering twelve neat takeaways just in time to close the books, even therapists suddenly pressed into service as narrative consultants, tasked with helping us wrap twelve uneven months into something that resembles a story. We are desperate to make the year say something coherent, as if coherence could be retrofitted after the fact, as if a clean arc might redeem long stretches of inertia, hesitation, or avoidance, and as if naming the lesson, preferably in a sentence tidy enough to share, might compensate for the harder, less photogenic truth that the lesson was understood intellectually and still not lived.

I understand the impulse. I participated in it. And I distrust it.

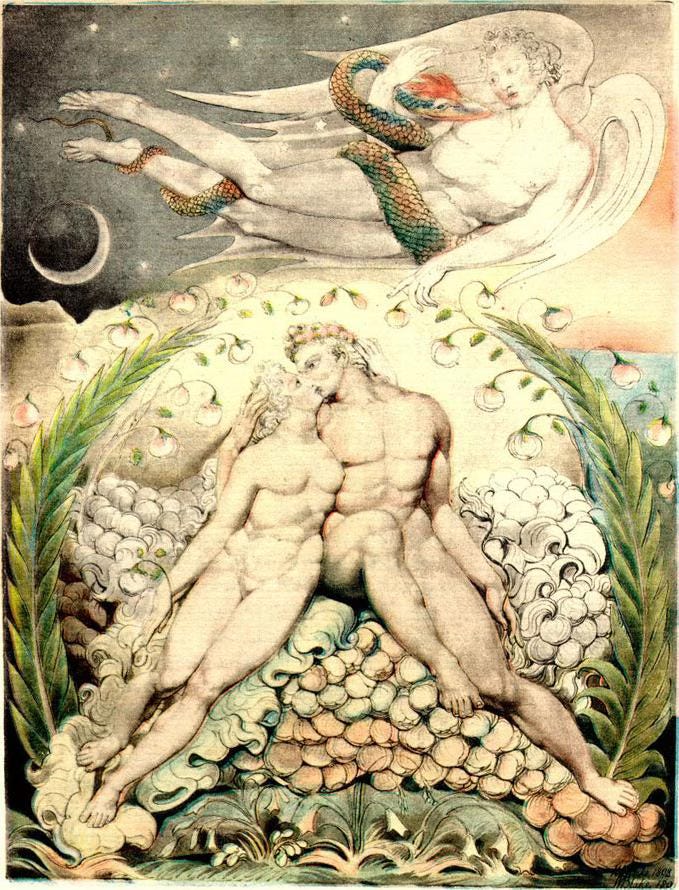

Because what December actually reveals is not that we failed to finish things, but that we overestimated our capacity to live multiple lives at once. We are exhausted because we carried too many possible selves in our heads and mistook that mental abundance for action. We rehearsed instead of inhabiting. We imagined instead of committing. We stayed available to everything and therefore unavailable to ourselves.

There is a particular cruelty in being good, too good, at imagining alternate futures, because the mind learns to substitute rehearsal for risk, spinning out versions of life that feel active enough to pass for progress while leaving the body exactly where it started. You run the scenarios, tweak the endings, tell yourself you stay open, stay curious, keep options on the table, when in fact you tread water with impressive technique. By the time December rolls around, those imagined futures start lining up silently, and they are not accusations but witnesses, the type who don’t raise their voices or point fingers, who simply stand there, hands in their pockets, letting the gap between what was pictured and what was lived do the work on its own.

Culture encourages this fragmentation. It celebrates optionality. It frames commitment as a loss rather than a gain. Better to keep doors open, identities fluid, plans provisional. December is when this logic collapses under its own weight. You realise that openness without direction is not freedom. It has become dispersal. A slow leaking of energy across too many fronts.

I once spent a December obsessively reorganising my bookshelves. Not reading. Reorganising. Alphabetising, then de-alphabetising, then grouping by imagined thematic constellations that made sense to no one but me. It felt productive. It was not. It was a way of touching my life without entering it.

There is humour in this, yes, but also something bleak…. a life handled like an archive instead of lived like a body.

December does not ask for perfection, despite what the surrounding culture of lists, reckonings, and premature self-improvement would have you believe, but for something far less flattering and far more difficult: the unpolished honesty that doesn’t arrive on demand and cannot be gamed. And honesty, inconveniently, refuses to show up while you are still in motion; it requires a type of stillness most of us avoid, because stillness strips away the background noise that usually protects us from our own thoughts. You cannot outpace December by staying busy, nor can you reframe your way out of it with clever language or last-minute insights; it simply waits, patient and unseducible, letting you exhaust your evasions until there is nothing left to do but stand still long enough to hear what has been trying, all year, to get your attention.

This is where the language of violence becomes appropriate, not in the melodramatic sense, but in the way pressure, compression, and exposure can feel invasive. Time corners you. It strips away future-based excuses. It forces a reckoning not with who you will be, but with who you repeatedly chose not to be.

The strangest part is that this reckoning rarely centres on external achievements. It isn’t the promotions that didn’t materialise, the publications that stalled, or the visible milestones that failed to click into place that ache the most when December closes in. What stings are the internal betrayals, the small, cumulative acts of self-evasion that never make it onto a résumé: the conversation you rehearsed for months and still didn’t have, choosing peace over truth until even peace grew thin; the email you never sent because it might have shifted a dynamic you’d learned to live inside; the courage you rationed carefully, like something scarce, saving it for a future version of yourself who never quite arrived. It’s the desires deferred not out of wisdom but out of discomfort, put off until they started to feel inconvenient, then faintly ridiculous, then vaguely shameful, before being quietly exiled under the guise of maturity, timing, or realism, none of which fully explains why they still surface, uninvited, when the year runs out of distractions and there’s finally nowhere left to hide them.

We don’t talk enough about desire as unfinished business, perhaps because it refuses to behave like a hobby or a reward and instead keeps inserting itself where it’s least convenient. We treat it as a luxury item, something to be indulged once the serious parts of life are settled, once the bills are paid, the children grown, the credentials earned, the chaos tamed, telling ourselves it will still be there when we finally have the time, the energy, the permission. December exposes that lie with brutality. Desire does not wait its turn, does not respect sequencing, does not politely step aside while you “get your life together”. It keeps accounts in the background, marking every deferral, every rationalisation disguised as prudence, every time “later” was used as a socially acceptable stand-in for “never”, and it remembers what you wanted, and how often you chose comfort, approval, or manageability instead. By the time the year closes in, desire doesn’t need to shout or make demands; it simply shows up as a dull ache, a restless irritation, a sense that something essential has been misfiled, not lost exactly, but postponed long enough to start feeling accusatory in its silence.

There is also a gendered undertone here that deserves mention, though it rarely gets it. Women, especially, are socialised to experience unfinishedness as personal failure rather than structural overload. You didn’t do enough. You didn’t choose well enough. You didn’t manage your time, your energy, your ambition properly. December arrives with this accusation pre-installed.

I reject that framing. And it’s not that I want comfort, but I surely want accuracy.

The real problem is not that we are inefficient, but that we are asked to be too many things without being allowed to prioritise without guilt. The culture applauds versatility and then punishes focus. It praises ambition and then pathologises intensity. It demands self-actualisation while sabotaging the conditions required for it.

December brings this contradiction into sharp relief. You can feel both complicit and trapped. Responsible and constrained. Guilty and angry. This moral ambiguity is uncomfortable, which is why most people resolve it with resolutions. Clean lines. Clear goals. A fantasy of starting over.

But nothing starts over.

January does not reset you. It inherits you.

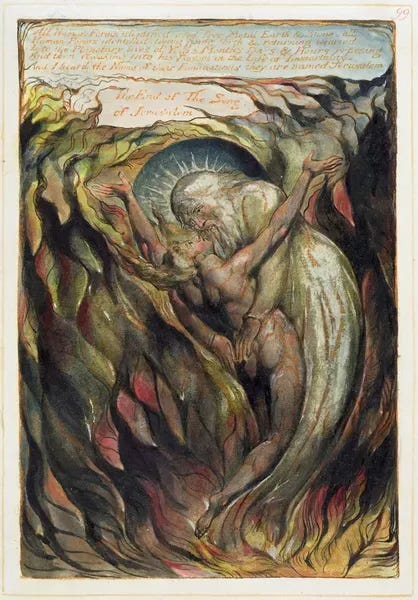

And here’s where I risk alienating some readers: I do not believe resolutions are harmless. I think they often function as emotional debt restructuring, moving the burden forward without paying it. They allow us to bypass grief. Because make no mistake, what December demands, before anything else, is mourning. Mourning the selves that will not be lived. The paths now closed by time, not by lack of imagination but by accumulated choice.

We resist this grief because it feels indulgent or dramatic. It isn’t. It is a form of respect for reality. You cannot honour your life without acknowledging its limits. And limits, unlike fantasies, do not negotiate.

There is a scene I replay every December, one that repeats itself with minor variations as if the city and the season were running a little experiment on me. I’m walking, usually at dusk, usually alone, my pace unremarkable, my thoughts loosely gathered, the day not particularly dramatic in either direction. Paris helps, of course it does, but this would happen anywhere, because the effect has less to do with beauty than with timing. The light is wrong in that specific December way: too low, too sharp, catching on edges it normally slides past, pulling details into focus that you didn’t agree to look at, the uneven stone, the tired shopfronts, the small compromises in the architecture of daily life. And in that light, I feel, quite suddenly, not sad exactly, not nostalgic or sentimental, but sober, as if something mildly intoxicating has worn off without warning, leaving behind that faintly exposed, slightly unsteady clarity that comes after. It’s the intoxication of possibility lifting, the sense that the year has stopped flirting with what might happen and has turned, instead, to what actually did, or didn’t, and there is no music swelling to cushion the moment, just the unmistakable awareness that some doors were never walked through, and that the body, unlike the imagination, remembers this with uncomfortable precision.

Sobriety is underrated. It is not joyless. It is precise.

Precision is what December offers, if you let it, not clarity in the curated, slogan-ready sense, but something rougher and more useful: a sense of where you are lying to yourself, where you are performing aliveness instead of risking it, where you are confusing motion with change.

This is not a call to radical overhaul. I distrust those. They rarely survive February. It is also not a defence of resignation. That’s just despair with better manners. What December invites, insists on, really, is a narrower, more uncomfortable question.

What is one thing you can no longer pretend not to know?

Not ten. Not a list. One.

For me, this year, it was the realisation that I have been using productivity as a moral shield. That as long as I was doing something, I didn’t have to confront what I was avoiding. That I could remain impressive while staying safe. This is not flattering. It is accurate. And accuracy, while not soothing, is stabilising.

Once you see it, you can’t unsee it. That’s the violence. And also, the gift.

December does not promise transformation, does not guarantee redemption, and does not even particularly care whether you change at all; it has no interest in reinvention arcs or personal brand upgrades. What it does, with a kind of bored efficiency, is strip away enough noise for the truth to register, when the social calendar thins, when the adrenaline drops, when the usual distractions stop doing their job. The truth shows up in small, unheroic ways: in the way certain conversations keep replaying themselves when you’re trying to fall asleep, in the irritation you can’t shake around people you used to tolerate easily, in the sudden clarity about a job, a relationship, a habit you’ve been defending out of inertia rather than belief. December doesn’t follow up, doesn’t offer guidance, doesn’t check whether you acted on what you noticed; it simply steps aside and leaves you alone with what surfaced, entirely indifferent to whether you turn that recognition into change or carry it, unresolved, straight into the next year.

The danger, of course, is to aestheticise this moment. To turn December melancholy into a brand. A vibe. A seasonal personality trait. The internet is full of this – soft despair packaged with candles and playlists. It’s seductive. It’s also evasive.

Because real reckoning is rarely beautiful. It is often boring, repetitive, unshareable. It involves saying no to things that once made you feel interesting. It involves disappointing people. It involves admitting that some of your favourite stories about yourself are no longer operational.

I won’t pretend this feels good. It doesn’t. But it feels real. And real has a gravitational pull that optimism lacks.

So where does that leave us, as the year closes in without waiting for our permission?

Not with hope as a slogan. Not with despair as a personality. Something narrower. A form of hope that does not promise expansion, only integrity. Not everything is possible, but something is still available.

That something is not a new self. It’s a truer relationship to the one you already are. Less adorned. Less defended. Less performative.

I am entering the new year without a list, which is not a virtue, not a statement, not an aesthetic choice pretending to be wisdom. It’s an experiment, born less of confidence than of fatigue, the particular fatigue that comes from watching well-intentioned plans harden into moral obligations you end up serving rather than using. Instead of resolutions, I’m carrying one unresolved truth with me, not polished, not fully articulated, but persistent enough that it keeps tugging at my attention, asking to be taken seriously. I’m curious, cautiously, sceptically curious, about what might happen if I let that truth transform how I spend my attention: what I say yes to without thinking, what I stop defending out of habit, what I no longer reach for simply because it once made me feel competent, admired, or safely in motion. That reallocation might lead somewhere remarkable, outwardly legible, easy to name. Or it might lead somewhere smaller, more contained, less visible to anyone but me, a shift in posture rather than circumstance, a narrowing rather than an expansion. I don’t know which, and I’m resisting the urge to dress that uncertainty up as bravery.

And that, finally, feels honest because it refuses the comfort of pretending I already know what this next stretch is for, or what shape a life is supposed to take once the year turns over and everyone else starts declaring their intentions out loud.

The year ends before we are ready because readiness is not the point. Presence is. Not perfect presence. Not constant presence. Just enough to stop pretending we didn’t hear the question when December asked it.

The rest, whatever comes next, will have to negotiate with that.

Unfinished but paying attention, still standing in the time we have, without answers, awake enough to listen, even now,

Tamara

This is devastating in the amazing, competent way only you seem to manage, Museguided, yes, but also unsentimental, almost prosecutorial. You don’t console the reader; you subpoena them. And somehow make that feel like care.

You ask, finally, the only question that matters: What is one thing you can no longer pretend not to know?

For me, reading this, it was this: that I have been using explanation as a substitute for choice. If I can narrate why something hasn’t happened, contextualise it, intellectualise it, give it a lineage, I don’t have to cross the uglier threshold of deciding. Your essay made it painfully clear that fluency is not the same as honesty, and insight is not the same as entry. I’ve been very articulate at the edge of my own life.

What I admire the most is how you refuse the usual December binaries—despair vs hope, collapse vs reinvention—and instead locate something colder and truer: pressure. Not motivation. Not inspiration. Compression. The sense that the year hasn’t failed us so much as stopped indulging our rehearsals. That line about imagined futures lining up as witnesses rather than accusers is exacting and original. You reframe regret as evidence. Evidence of attention misallocated.

And the Paris dusk, oh, how I miss my city, is a masterstroke… that December clarity is the anesthesia wearing off. Possibility sobers up. What’s left isn’t bleak; it’s precise. That precision, as you suggest, may be the only real kindness time offers.

This didn’t make me want to “do better”.

It made me want to stop pretending I don’t already know where the bargain has gone bad.

Which feels like exactly your point.

Tamara, thank you for a year in which I’ve grown and evolved beyond my imagination thanks to your essays!

The real thing being exposed in the December audit is the clash of desire against grandiosity. We have, both an unlimited capacity to want, and therefore remain unsatisfied, as well as unlimited optimism, or maybe delusion, that next year will be different. This recurrence stems from exactly what you pinpoint: the belief that time is linear and progressive, not cyclical. Inherent to the progressive paradigm is the presupposition that things must get better in some measurable way, otherwise you've failed or are stagnant. This completely contradicts our lived experience of never quite being satisfied; of always wanting more, yet remaining stuck in a loop of reactivity and unmet expectations. What's grandiose is our absolute certainty in linear time, and our expectation that next year will be the year we turn things around, despite "failing" to do so in every previous year.

I love your framing of touching your life instead of living it; organizing the book collection instead of reading it. This is why selling programs or memberships or seminars is so effective, and it's why people love to obsessively plan and resolve: it gives us the illusion of progress or productivity; it makes us feel closer to our goals without actually walking down the path, and it's psychologically comforting because every step forward is a step you will need to retread when you retreat, and we always love having the option to retreat.

December is the reckoning. It wouldn't be or shouldn't be if we could just recognize the cycle and not insist that we are on some linear path, where the choice is only advancement or retreat. We also should recognize the perpetual nature of desire, which is just as cyclical as time, with its seasonal nature depending on the ebb and flow of our appetites. Winter will come again; you will be hungry once again and this isn't a trap, but the pulsating proof of life. The year ends before we are ready because we are never ready; we are never satisfied.

Brilliant as always. A true holiday gift. Thank you, Tamara.