The Past Lies, The Future Laughs

Misreading history and mistaking certainty for wisdom

We misread the past to predict the future. Mistake after mistake, like toddlers with tarot cards, we flip history’s pages hoping patterns will behave, forgetting that hindsight is a seductive liar, always neat, always linear. But history isn’t a manual. History is a murmur, full of contradictions we compress into palatable parables. We call them “lessons”, but really they are just flattering myths about how much control we think we have. The future, meanwhile, is busy laughing in irregular verbs. It conjugates chaos: I was wrong, you were wrong, we will all be wrong again. Predictive logic doesn’t survive contact with entropy, and yet here we are, forecasting our destinies like financial analysts in the middle of a thunderstorm, umbrella turned inside out, spreadsheet soaked.

The Enlightenment gave us this dangerous idea that knowledge would save us, that the more we knew about the past, the more prepared we’d be for the future. This is charming. Like saying the more intimately you understand your last heartbreak, the less likely you’ll fall for a new kind of liar. Except, of course, you don’t fall for the same mistake twice… you evolve! You fall for a higher-resolution version of it. “We learn from history”, we say, while rebuilding Babel in silicone and giving it Wi-Fi. We don’t learn. We stylise our delusions with data sets.

I once thought my personal history was useful. That if I could trace every emotional pattern (the narcissist lover, the gentle coward, the unavailable father, the public performance of intimacy), I’d crack some secret code. Heal. Avoid. Calibrate. It took me a long time to realise I was just applying the same algorithmic fallacy to my own life that we apply to empires. Autopsy as oracle. But heartbreak is not algebra. You don’t solve for X. You live with the bruised alphabet.

Civilisations, like people, repeat themselves with variation, not precision. They don’t reenact their failures; they reinterpret them, adjusting the costume, changing the soundtrack, insisting this time the outcome will be different. The Roman Empire didn’t fall because of a single moral failure, just as your last relationship didn’t implode because of that one fight in February. History rarely collapses on cue. What actually happens is attrition: small compromises dressed as pragmatism, fatigue misread as wisdom, decay that feels reasonable while it’s happening. But we can’t tolerate that kind of messiness in retrospect. So we revise. We clean the narrative. We reduce a long, uneven decline into a moral fable we can point at. Edward Gibbon made Rome’s collapse a story about decadence because it allowed him to stand at a safe moral distance, just as I made my breakup a story about his cowardice because it spared me the humiliation of examining my own exits, my half-truths, my willingness to stay when leaving would have been braver. This is what memory does under pressure, it edits for coherence, not honesty. Selective memory is a survival instinct. But it’s a terrible guide. A coping mechanism mistaken for a compass, disregarding truth, but pointing toward whatever version of the past lets us sleep at night.

Lately, I’ve been wondering whether the real mistake isn’t how badly we read history, but the faith we place in reading it at all. Or more precisely, in reading it like scripture instead of like jazz: improvisational, contradictory, full of syncopated tension, dependent on listening as much as on structure, and liable to fall apart the moment someone tries to notate it too cleanly. We want timelines that teach and epochs that echo. But the past doesn’t want to teach you anything. It isn’t waiting to be decoded or redeemed. It mostly wants to be left alone, occasionally muttering from its grave when someone drags it out of context on X or any other social media platform en vogue these days.

Take 20th century fascism, which we now reduce to a cautionary tale, a Netflix genre, a meme with bad hair. “History repeats itself”, they chant, mistaking kitsch for prophecy. But repetition is not recurrence. Our era doesn’t echo the 1930s, it riffs on it in major key. The aesthetics are sleeker, the algorithm more insidious, the dystopia crowd sourced. If Mussolini had TikTok, he’d have been verified by lunchtime.

The same flattening happens everywhere. We treat revolutions as if they follow a three-act structure – oppression, uprising, liberation – conveniently forgetting the long, messy middle where ideals mutate into bureaucracy, and slogans learn to survive without belief. We turn the French Revolution into a morality play about excess, the Cold War into a chess match with clear winners, the fall of the Berlin Wall into a triumphal freeze-frame, as if history ever stops moving just because we’ve chosen a flattering still.

Financial crises get the same treatment. We speak of bubbles and crashes as if they were natural disasters rather than collective hallucinations with spreadsheets. Each collapse is framed as a lesson learned, a guardrail installed until the next one arrives wearing new jargon, new instruments, new confidence. Tulips become mortgages become crypto, and every time we insist this version is different because it’s smarter, faster, more mathematically insured against human weakness.

Even our utopias repeat themselves badly. Every technological leap arrives promising emancipation, the printing press, the factory, the internet, and every time we act surprised when it also produces surveillance, conformity, new hierarchies of voice. We wanted connection; we got metrics. We wanted knowledge; we got amplification. The mistake isn’t that we didn’t foresee the consequences, I think we are very much aware of those, but we keep mistaking novelty for innocence.

That’s the danger of historical analogy when it festers into ritual. It gives us the comfort of recognition without the burden of attention. It lets us say this again instead of asking what is this now?

We don’t actually want to understand the present, we want to domesticate it by comparison, file it under something already known, already survived. But history doesn’t come back to be recognised. It comes back wearing a different face, speaking a different dialect, daring us to notice what no longer fits the script.

Our hunger to extract patterns from pain has the shape of belief. It asks suffering to justify itself, to arrive bearing meaning, to submit to interpretation. Pattern-making is how chaos gets house-trained, how plagues become “turning points”, economic collapses become “corrections”, migrations become “cycles”, and mass grief gets folded into phrases like unprecedented times and necessary disruption. We tell ourselves that the pandemic, the war, the collapse of trust, along with climate disasters, financial implosions, cultural purges, and personal losses too ordinary to make the news, belong to some grand syllabus, a moral arc bending toward coherence if we squint hard enough.

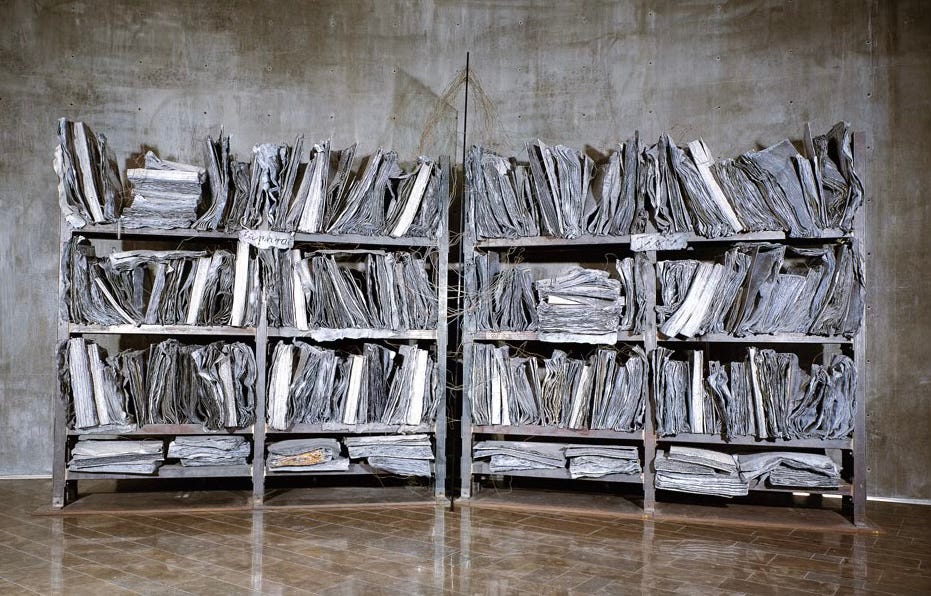

But history has no curriculum. No final exam. No promise of improvement. History is a disorganised library where half the books lie, the rest are missing pages, and the catalogue was last updated by someone with an agenda. We wander its aisles anyway, mistaking proximity to explanation for understanding, pulling random volumes off the shelf, and absurdly hoping to find meaning filed neatly under fiction.

Even personal memories, those supposedly stable sediments of identity, are riddled with misinterpretations. They don’t sit there intact; they shift and crack and occasionally release a smell you had forgotten was trapped inside them. I recently found an old journal entry from my early twenties that claimed I had “finally understood love”. The paragraph was so earnest, so hilariously sure of itself, it read like a manifesto written in a locked bathroom at 2 a.m. I nearly wept from embarrassment. Or laughter. Or both. What unsettled me the most wasn’t that I’d been wrong, that’s forgivable, but how convincingly I’d mistaken intensity for clarity, conviction for insight. I still don’t know what’s worse: being so wrong or being so certain about being right?

The algorithmic age has made this worse. With every click, every search, every passive scroll performed half-asleep, we feed a machine whose sole ambition is to make the past look like foresight. Spotify thinks it knows what we want next. Google finishes our questions before we’ve decided whether they were worth asking. Our phones murmur back to us a future already approved, curated from yesterday’s habits, last year’s fears, last decade’s appetites. This is not prophecy! Nostalgia has an immense processing power. We call it progress, but it behaves more like an anxious accountant, endlessly reconciling yesterday’s data to avoid the embarrassment of surprise.

We’re not moving forward; we’re looping, buffering, circling the drain of our own behavioural feedback systems, mistaking frictionless repetition for momentum.

On a geopolitical level, this regression graduates from convenience to doctrine. Some states now govern the way platforms recommend content: risk-averse, pattern-obsessed, allergic to deviation (especially in Europe). Foreign policy is modelled. Voters are segmented before they are addressed, dissent is predicted before it’s expressed. Intelligence agencies don’t ask what might happen, they ask what usually happens, then act surprised when history refuses to stay within tolerance levels. Revolutions are flagged as anomalies, humanitarian crises become data points, entire regions are reduced to dashboards blinking amber, then red, then mercifully out of view.

The irony, of course, is that the more predictive the system claims to be, the narrower its imagination becomes. Algorithms penalise anticipation. They reward consistency, familiarity, escalation, inertia. The unexpected isn’t interpreted as information but treated as noise to be filtered out, managed, sanctioned, or buried under averages.

This is how uncertainty becomes a threat, curiosity a liability, and change something to be pre-empted rather than understood.

So, we end up personally and collectively governed by machines trained on our least courageous selves. Our browsing history becomes destiny. Our worst impulses get better infrastructure. And when the future finally arrives bearing something genuinely new, a refusal, a reordering that doesn’t resemble the past, we greet it with disbelief because it didn’t appear in the model. Contrary to mainstream thinking, failure is not technological but moral…. we outsourced imagination to systems designed to eliminate it and then wondered why everything started to feel so eerily familiar.

My grandmother, who grew up under a regime that rewrote history as performance, used to say, “You can’t trust anyone who thinks they understand the past too well.” She was talking about certainty. The kind that arrives fully formed, already polished into aphorism, already convinced it has extracted the moral. She meant the people who speak in tidy lessons, who narrate complexity as if it were an inconvenience, who turn memory into doctrine. The men who write or speak with too much confidence. The lovers who explain your own life back to you before you’ve finished living it. There is something violent about premature interpretation, it forecloses possibility, seals meaning too early, turns uncertainty into error instead of information. Once the story is declared finished, nothing genuinely new is allowed to happen.

You can see the same reflex at work internationally, especially in the way America currently behaves beyond its borders, less like a participant in a shared disorder, more like a self-appointed hall monitor of history. It condemns other nations for imposing order through force, surveillance, intimidation, then proceeds to do the same, only with better branding and better vocabulary. Chaos elsewhere is framed as pathology; chaos at home becomes necessity. Intervention is renamed stability. Power insists it is reluctant, benevolent, exhausted by its own virtue. The thuggishness is managerial now: sanctions instead of sieges, algorithms instead of informants, moral language deployed as crowd control. And when the consequences arrive (resentment, blowback), they are treated as aberrations, never as mirrors. When a nation mistakes its narrative for reality, it starts policing the world the way insecure people police conversations, demanding order everywhere while reproducing the very behaviour it claims to be correcting.

Europe, meanwhile, has perfected a different evasion, not the brutality of force, but the comfort of administration. It governs through procedures, communiqués, white papers, and the soothing fiction that complexity equals care. Its leadership speaks fluently in diplomatic upholstery, calibrated statements, balanced positions, eternal consultations, while remaining increasingly illiterate in the language of population’s fear, fatigue, and ordinary precarity. Control is outsourced to frameworks, responsibility dissolves into process. The obsession with money laundering, compliance, transparency regimes, and regulatory hygiene is sold as moral vigilance, but often functions as a respectable excuse for extending surveillance and restriction downward, where it’s the easiest to enforce, while capital continues to move freely upward, untouched and unnamed. Immigration, too, is narrated as humanitarian necessity while silently serving a more convenient truth: Europe needs bodies to do the work it has offshored morally and abandoned culturally, labour it no longer wants to see itself performing, administered by people it is happy to depend on but reluctant to fully include. The result is a continent run like a filing risk-averse, self-satisfied, allergic to confrontation system, a tampon between great powers, too refined to throw a punch, too timid to take one, mistaking diplomacy for courage and inertia for stability. It neither enters the ring nor leaves it; it hovers, procedural and paralysed, convinced that if it just manages the forms well enough, history will eventually forget to ask for substance.

And perhaps that’s what this is really about…. our war against surprise.

We don’t want the future, not in any honest sense, instead we want a continuation of what we already understand, the same story with a software update, the same hierarchies with better optics, the same mistakes with improved justifications. We want change that confirms us, disruption that flatters our prior positions, revolutions that arrive pre-approved and leave the furniture intact. Surprise, by contrast, is how the universe edits. It interrupts the narrative, cuts scenes we were still emotionally invested in, inserts characters we didn’t audition and removes ones we’d already written sequels for. Markets don’t crash politely. Diseases don’t respect preparedness plans. Technologies don’t ask whether we’re ready to be altered by them. Empires don’t collapse at the moment of maximum symbolism. Asteroids don’t ask for context. Lovers don’t always say goodbye. And history, when it repeats, rarely uses the same accent… it mutters, stutters, disguises itself as something manageable, and only later reveals how thoroughly it has rewritten the plot.

Which brings me, inconveniently, to hope. Not the polished one that fits on banners or survives a press conference, and not the aspirational glow politicians deploy when they’ve run out of answers. I mean the hope that arrives uninvited, after evidence has already testified against it. The hope that survives because it refuses to die. It’s the irrational after-image that lingers once belief has been stripped bare: artists who keep working under tyranny without expecting freedom, because silence feels worse; a woman who loves again out of defiance toward what tried to close her; people who still show up with signs knowing full well they’ll be misquoted, cropped out, or ignored entirely. This is not optimism! It doesn’t promise improvement. It doesn’t even claim effectiveness. It’s closer to a tic, a compulsion, a stubborn refusal to fully comply with despair, an act performed without guarantees, without applause, without the comfort of thinking it will matter, and done anyway.

I don’t know how this ends. None of us do. Maybe that’s the point. Maybe the future isn’t a sequel or a moral pay-off. Maybe it’s just a rehearsal we never quite finish, each generation fumbling the lines, hoping the stage holds. Maybe the best we can do is stay awake. Hold history not as a weapon or a mirror, but as a wound that keeps whispering: don’t assume you understand me.

So no, I won’t end this by saying we must “learn from the past.” That’s a thesis statement, and thesis statements belong to systems that still believe history behaves. What I’m reaching for is messier than instruction, closer to a question that won’t hold still. A stammer. A hesitation you can’t smooth out without lying.

What if the past isn’t there to guide us at all, not as map, not as warning, not as precedent, but to interrupt us? What if its real function is to puncture our confidence just when it starts to harden into doctrine?

Maybe being repeatedly, extravagantly wrong isn’t a failure of intelligence but a condition of living without illusions. Maybe misunderstanding is not what condemns us, but what keeps us pervious enough to remain human. The danger isn’t that we repeat ourselves. It’s that we declare ourselves finished interpreters, convinced we’ve extracted the meaning and can now proceed safely, efficiently, morally insured. History doesn’t punish us for ignorance nearly as much as it punishes us for certainty. And if there’s any discipline worth practicing, it might be this: to stay awake inside what we don’t yet understand, to resist the urge to close the story too early, to accept that humility, and not mastery, may be the only posture that keeps the future from hardening into the past before it even arrives.

Because maybe it isn’t repetition that dooms us, maybe it’s the arrogance of thinking we’ve understood it……

Written in doubt rather than conviction, left open to whatever refuses to behave, offered without guarantees and in recognition that uncertainty may be the only honest signature,

Tamara

I'm someone who usually doesn't come to the defense of ideology, religious or otherwise, but I've always said that the best case for religion isn't what it says about the nature of reality; rather, its strongest position is what it has to say about knowledge. The reason knowledge is dangerous isn't merely that knowledge is power; it's that knowledge is always incomplete. It's the people who have a small amount of knowledge who think they know everything, because they misguidedly apply pattern recognition techniques at scale. It's an error of excessive extrapolation that you get with the myopia of knowing enough to navigate some small area around you, but not enough to really see the forest through the trees.

Knowledge is incomplete, and whatever knowledge we do have requires interpretation, and that interpretation requires context that has to extend way beyond the span of our lives, and encompass more than merely our self interest. Of course we can rarely if ever manage this, so then we overcompensate with certainty and then force that certainty on the world around us in an attempt to exert and maintain control.

I love what you said about not wanting the future, because it's congruent with our lack of real interest in the truth. Because we can never have the full picture, we fill the picture ourselves, then demand that the world conform to it as a blueprint. Similarly, we want time to march in a linear progression that follows the causal logic of our limited understanding of the variables, and our biased presuppositions. This is precisely why we've surrendered ourselves to algorithmic selection, because it's a continuation of the oldest precepts of religious ideology: the world is unpredictable, knowledge is dangerous, so trust in the WORD. In the modern world, it's trust in the curation; it's to feed on the FEED, with it's self-fulfilling feedback loops.

There's so much more to say, Tamara. This is one of your best. I feel like I say this at least once a week, but you simply keep my gears oiled and spinning. The error is in thinking that there's an actual limit to your abilities. I can't be sure of the future, but it's hard to see one where you're not dominating this platform.

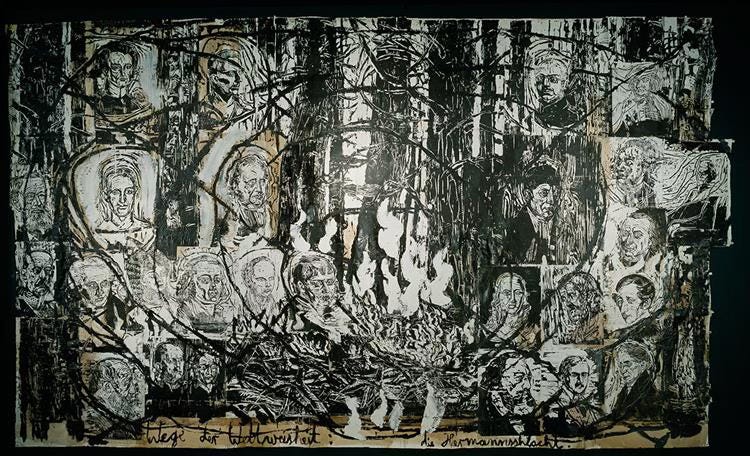

Tamara, this is one of your best. Reading it felt like standing in front of a painting that refuses to resolve if you stare too long. The kind where the closer you get, the less explanatory it becomes. It reminded me of Francis Bacon’s portraits where faces are smeared, features technically present but morally unstable. You can still recognise the human, but certainty has been violently removed. That’s what this essay does to history. It doesn’t deny its shape, it distorts it until our confidence in interpretation starts to melt.

What I admired the most is how the structure mirrors the thesis. You don’t march us toward a lesson; you circle, hesitate, double back, let ideas fray at the edges. That restraint is rare. Most writing about history wants to win. This wants to stay awake. It understands that clarity, when it arrives too smoothly, is often just obedience in a well-lit room.

Your argument about analogy as anesthesia landed hard for me. We reach for the past to the way museums reach for plaques, to make the chaos legible enough that we don’t have to feel implicated. It’s like how we turn Guernica into an icon of “anti-war” sentiment, stripping it of its ongoing violence, flattening it into a symbol you can nod at without being disturbed. The painting doesn’t change, but our relationship to it becomes hygienic. History gets the same treatment: framed, captioned, rendered safe.

The sections on algorithms and prediction felt especially personal because they echo what’s happened to art itself. Streaming platforms don’t recommend what might undo us, they recommend what statistically resembles what we already tolerated. The future is no longer commissioned; it’s extrapolated. And just like you describe, surprise gets treated as a flaw. The new, the dissonant, the genuinely unfamiliar, those things don’t perform well in systems trained on recognition. They get filtered out because they’re unclassifiable.

Your invocation of jazz is amazing, but I kept thinking of performance art instead. Marina Abramović sitting silently across from strangers, offering nothing to interpret, no moral, no arc—just presence. The work only exists if you’re willing to stay in discomfort without resolving it into meaning. That’s the posture you’re arguing for politically and historically, attention without premature narration. Most people can’t tolerate that. They want the label, the takeaway, the reassurance that they understood correctly.

And the personal passages matter precisely because they refuse redemption. The journals, the relationships, the embarrassment of former certainty do the work of proving the larger claim, that interpretation is often just a way of preserving dignity. We edit the past to survive. That doesn’t make us evil; it makes us unreliable. The danger begins when we confuse that coping mechanism for insight.

By the time you arrive at hope, it feels earned because it isn’t heroic. It’s closer to what artists do under regimes that don’t care whether they exist, they keep making work that may never be seen because not doing it would feel like a deeper lie. That version of hope doesn’t believe in progress. It believes in not going numb.

Your essay doesn’t ask to be agreed with. And that’s your brilliance. It asks to be held without being resolved. And that may be its most fantastic gesture. We are obsessed with conclusions, you’ve written something that insists on staying unfinished as an ethical stance. Discipline and extraordinary writing. Brava, Tamara. Encore une fois.