The Body in Rehearsal

How we imagine ourselves into flesh and out of line - how the body becomes script, stage, and subversion

Some people have a body; others have a body project. And for the rest of us, those whose internal lives leak, slip, and gesticulate before we even open our mouths, the body is neither object nor project but narrative medium. Mine has always been a novella of contradictions: an upright spine that suggests authority, paired with hands that fidget like I constantly audition for absolution. I have walked into rooms hoping to disappear and somehow always ended up being noticed, not for what I said, but for how I held the air. Posture is premonition, I’ve come to learn. And no matter what they tell you, how you stand reveals what you fantasise you might become. Or worse, what you fear you already are.

This is not a metaphor. It is a psycho-physical reality so mundane it gets mistaken for personality. The imagination of the body isn’t some poetic flourish tacked onto identity like an epigraph, it is how identity inhabits the flesh. The ways we hold tension in the jaw, exaggerate the swing of our hips, modulate pitch, flatten affect – all these are subtle drafts of an internal screenplay we may not even be aware we are directing. Most people don’t realise they have been method acting their way through life. Fewer still understand that the character they play was written by an invisible chorus of mothers, lovers, gods, influencers, trauma ghosts, and dreams that smelled like future but arrived in disguise.

Take the artist’s body, for instance, not the body of an artist, but the body imagined as artistic. It is frequently a little undone, purposefully disheveled, one shoulder lower than the other as if permanently bearing the weight of interpretation. There is often a cultivated fragility, what I once called, in a lover, “existential posture syndrome”. I later learned it was scoliosis, which says more about me than him. But the fantasy persisted: that a tilted head means thoughtfulness, that unkempt hair signals a mind busy with poetry. We tell these lies with our bodies so well that we forget we once invented them.

Even the erotics of posture are ideological. The woman who imagines herself as untouchable develops a certain glacial slowness, a calculated delay in response, like a metronome tuned to disdain. The man who wants to be seen as powerful will broaden his stance, lower his voice, elongate vowels as if echo grants substance. But here’s the problem with fantasies… they solidify. They fossilise into behaviours so rehearsed they lose spontaneity. We become overly choreographed versions of our desires, like performers who can’t get off stage, even at home, even in bed. Especially in bed….

Real eroticism doesn’t pose. It leaks. It arrives uninvited in the smallest betrayals of poise – a breath caught too late, the wrist that forgets to be still, the glance that grazes rather than lands. True erotic presence is not choreographed; it is an interruption. A slippage. The moment when the body forgets the role and becomes the raw animal behind it. Not decorative, not devout, just there, alive and trembling with unsanctioned wanting. And because desire doesn’t follow ideology, this kind of eroticism embarrasses both puritans and influencers. It is not branded or posed; it is felt. Not in the flesh alone, but in the imagination the flesh dares to awaken. When someone’s presence feels like trespassing into your own unspoken need, that is not style, it is transgression. That, too, is authorship: to let your body say the thing your voice cannot risk.

And then there’s trauma… not the buzzworded, monetised variant served in carousel posts, but the real kind. The kind that rewrites the body’s grammar until everything becomes a whisper. I have seen people contort themselves out of joy. You can spot them by the subtle tightness around the shoulders, the false cheer in the voice, the impeccable timing of laughter. We have trained our bodies to be palatable before we learned to say no. The fantasy here is one of safety. And like most fantasies rooted in survival, it comes at the cost of freedom.

Which is why I don’t trust “authenticity” when people talk about bodies. The whole concept reeks of Calvinist minimalism dressed up as spiritual wisdom. What if the most truthful version of yourself is a performance? What if the imagination is the only thing that keeps the body from ossifying into what the world told it to be? I would rather perform a self I chose than inherit one shaped by algorithms and ancestral regret. And yes, I’m aware that even that sentence sounds like it belongs on a tote bag, but let’s not pretend the body isn’t already being marketed in bulk.

Social media has turned the body into a billboard of curated imaginings, and while it’s fashionable to critique the Instagram Arch™ or the soft-core capitalism of wellness influencers, the truth is older and murkier. Even before filters, women were taught to perform innocence with their clavicles and seduction with their ankles. Even before TikTok, men were told to square their shoulders and walk like consequence didn’t apply to them. These bodily fantasies are ancient – Rome had its own version of the “gym bro”. Sparta invented the aesthetic of militarised masculinity. And somewhere in between, someone imagined that a thigh gap meant virtue.

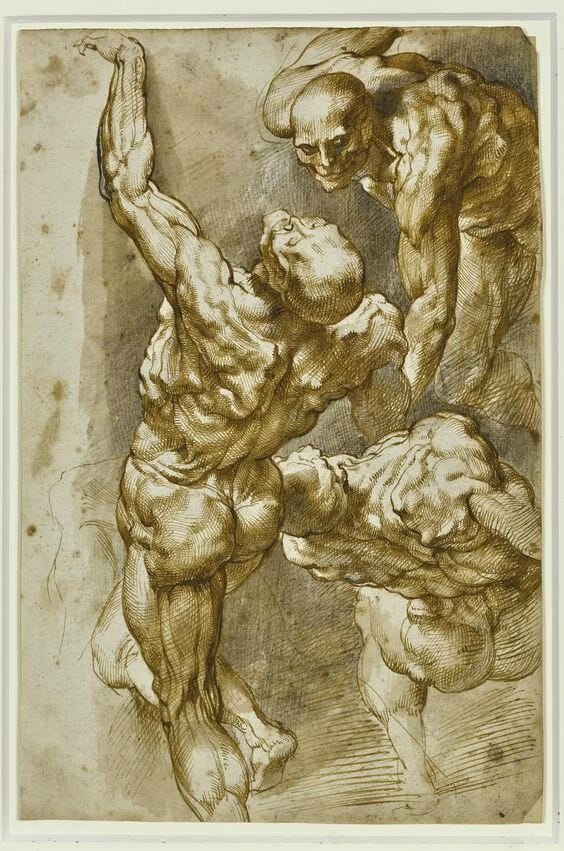

But if culture scripts the body, imagination is the rogue playwright. Think of dancers like Kazuo Ohno in Butoh, whose movements seemed to emerge from some subterranean mythic consciousness, grotesque and transcendent in equal measure. Or drag performers who rewrite gender with every eyelash. They challenge norms, yes, but they also expand what a body can mean. These are not self-expressions. They are re-writings of bodily epistemology, disruptions in the assumed choreography of flesh. The imagination here isn’t whimsical; it’s strategic, even defiant.

Of course, the body is never just a body, it is a social manuscript. Gender makes that painfully clear. To be read as a woman is to have your body pre-annotated by others: sexualised, sanctified, diminished, consumed. To be read as a man is to inherit the pressure of performance disguised as presence: stillness mistaken for strength, silence for stoicism. And if you fall outside those scripts, if your body dares to improvise, you become threat or spectacle. Trans, fat, disabled, queer – bodies that rewrite the expected syntax of gender are often punished for their fluency. But even within conformity, the performance is exhausting. How many women have spent decades shrinking to be seen? How many men have clenched their jaws through entire lifetimes of unspoken need? The body bears the cost of all this dramaturgy. Which is why to live gender consciously – not obediently – is itself a form of résistance. Every uncollapsed belly, every softened gait, every unapologetic flare is a line edited back into the script. The fantasy doesn’t have to oppress. Sometimes, it liberates.

I once fell in love with someone entirely through the way he inhabited space. He wasn’t beautiful in any conventional sense, but he moved like a secret that trusted you. His hands hovered before touching anything, as if asking for permission, and I remember thinking: this is a man whose body has been informed by both tenderness and refusal. You can learn a person’s entire childhood from the way they cross a street or hesitate at a door. And sometimes, they learn yours back.

This is where it gets tricky. Because once you become aware that your body is a story, you begin to revise. But revision is not always liberating. It can become obsessive. I have spent hours in mirrors, not out of vanity but out of desperation, to see if I could catch myself mid-lie. Trying to find a gesture that felt untainted by imitation. Spoiler: I didn’t. There is no “pure” movement left, no gesture untouched by mimicry or memory. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t real. It means they are human.

So we adapt. We shift. We throw out the fantasy of unmediated presence and instead begin to practice something more drastic: embodied contradiction. A posture that says, “I’m here”, and a flinch that says, “but not all of me”. A smile that’s both invitation and armour. The voice that steadies itself even as the hands betray. This isn’t performance as deception, it’s performance as survival. Or better yet, as authorship.

Philosophers have always mistrusted the body… Plato cast it as a noisy prison, Descartes dissected it from the mind, and Augustine feared it like a temptation he couldn't quite enjoy. Western thought has long treated the body as something to rise above or manage: a vessel for virtue, a suspect in sin. But even this suspicion reveals a secret reverence – the acknowledgment that the body is too powerful to be ignored. Every attempt to transcend it only confirms its dominance. Meanwhile, Eastern philosophies, often more generous, saw the body not as a distraction from enlightenment but its vehicle. In Tantric traditions, the body is a site of divine knowledge, of union, expansion, dissolution. The body remembers what the mind forgets. It holds the archive of our lives, of the entire history of meaning-making. And when we move, or dance, or tremble, we echo the same ache that carved myths into marble and prayers into breath. The body was always the first philosophy.

On the other hand we don’t talk enough about how time annotates the body. About how aging is not a slow erasure but a revision, sometimes brutal, sometimes exquisite, of the original text. Skin softens, scars stretch, strength recalibrates. What once felt ornamental becomes essential, and what once drew attention now holds memory. The imagination doesn’t retreat with age; it deepens. It begins to dream not of becoming someone new, but of finally returning to someone abandoned. I used to think that youth was the body’s most expressive phase, but now I know: it’s the aging body that tells the truth, unedited. The hips that no longer swing with ease. The voice that cracks mid-sentence. The neck that no longer holds high without effort. These are not failures. They are flourishes of survival. Time, too, has a choreography. And the body, faithful scribe that it is, remembers every beat.

Maybe that’s the best we can do: to become writers of our own presence? To acknowledge that every fantasy we have ever had about who we are has already written itself onto our shoulders, our hips, our vocal inflections. And to respond not by trying to be more “authentic”, but by becoming more deliberate. More aware of the scripts we have inherited and the ones we wish to edit. More willing to inhabit the roles that feel ridiculous, contradictory, too much. Because sometimes, the fantasy knows something we don’t. Sometimes, the imagined self has better instincts than the one who learned to apologise for breathing.

There’s a version of me I haven’t become yet, but I’ve seen her. In glimpses. In shadows. In the way I stand when no one is watching and in the way I dance when everyone is. She’s less composed, more dangerous. She moves with the kind of elegance that doesn’t beg to be liked. I don’t know if I ever fully become her. But the body remembers. And the imagination, wild thing that it is, keeps trying.

From the wrist that trembles, not from the hand that waves, carved in posture, whispered in motion, with unsanctioned wanting, still drafting and becoming,

Tamara

Wow. This essay… reading it felt like standing in front of a mirror that reflects not the body, but its echoes. It reminds me of how, growing up, I used to think posture was about politeness—back straight, shoulders back, chin up—the choreography of acceptability. But over time, I started to realize how much of my body language was less about social cues and more about emotional camouflage. A slouch not from laziness, but from shame. A raised eyebrow as punctuation for things I didn’t dare say out loud.

When I read “the body is a social manuscript” that hit hard. It made me think of how grief lives in my mother’s hands, or how my friend’s walk changed after heartbreak, slightly slower, as if pacing memory. The body testifies.

Your essay makes me wonder if we’re all accidental playwrights of our own embodiment, revising our roles not to deceive, but to survive. Maybe even to dream. Your writing stretches between philosophy and intimacy, like a spine that holds both knowledge and longing.

I don’t know if I’ve met the version of myself my body wants to become. But I believe she’s in rehearsal too. And thanks to this, I might start listening more closely to the script written in my silences

Thank you, Tamara, for another amazing essay.

God, Tamara, you really never disappoint with your essays: pure poetry, knowledge, surprises, thoughts, wonder and wander…

What a formidable voice you have.