Money Mirage

On power, performance, patronage, and the price of meaning – how we came to worship wealth and abandon worth

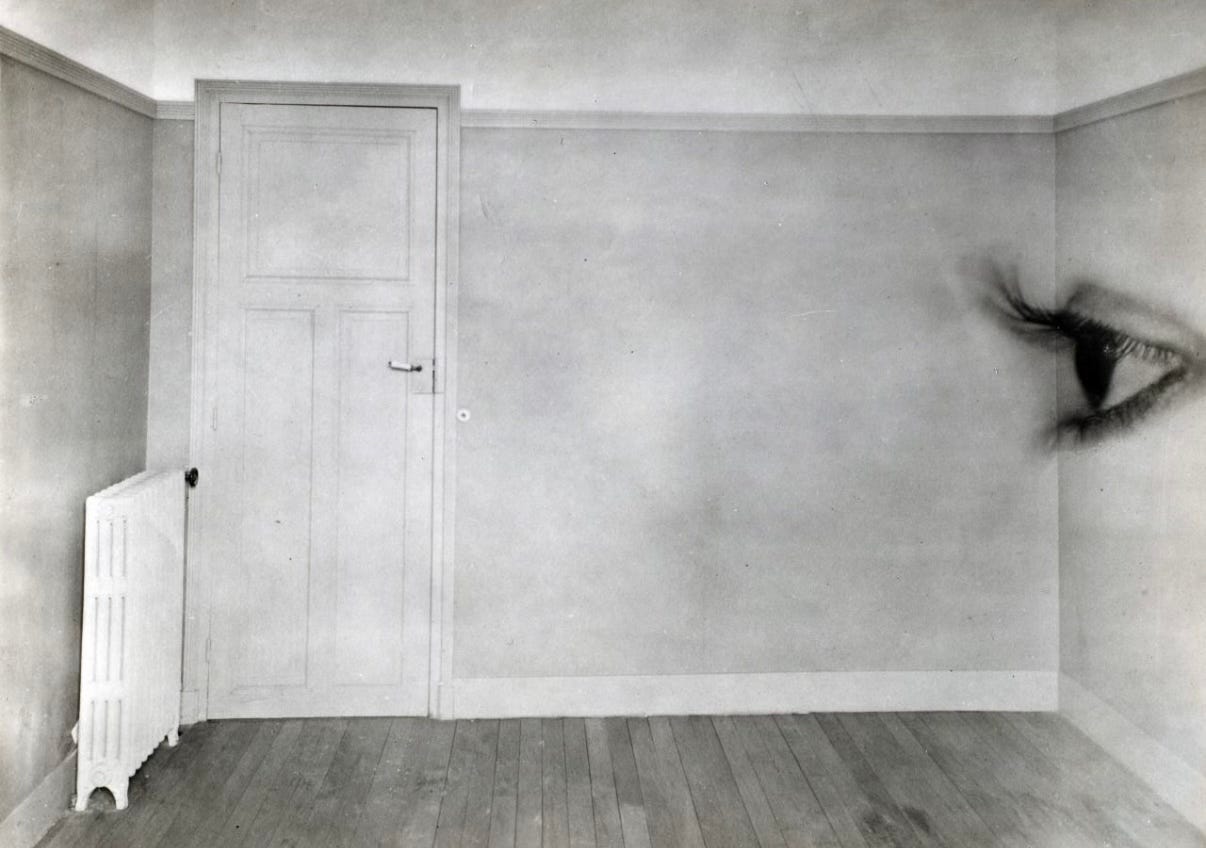

Every civilisation has its creation myth. Ours begins not with fire or gods, but with a spreadsheet. We don’t tell stories around campfires anymore, we check balances under fluorescent lights. And in this myth, money is the sun: neutral, natural, necessary. But tilt your head just slightly, and you’ll see it flicker, less like the sun, more like a shimmer on hot asphalt. Not substance, but seduction. Not truth, but trust dressed up as truth. Money isn’t what we think it is. It never was.

Let’s begin where most intellectual laziness does, with a myth so tidy, so suspiciously well-behaved, that its survival says more about our appetite for comfort than our concern for truth. The barter origin story – that charming parable where Arthur has too many apples and Betty too much bread, and through a spontaneous flourish of mutual convenience, they stumble upon the brilliance of exchange – is less an origin story than a sedative. It’s a bedtime narrative economists tell themselves to sleep better at night, a myth that flatters us into believing that money was born of cooperation rather than coercion, that markets emerged from needs rather than power. But scrape just beneath that cheery allegory and what you find isn’t a bustling village square filled with cheerful barterers negotiating fair deals, but temples, palaces, and states keeping ledgers of tribute, tax, and blood-bound debt.

Because the historical record, messy, inconvenient, and utterly uninterested in supporting TED Talk optimism, tells us a different story, one carved into clay tablets in ancient Mesopotamia where the earliest forms of writing weren’t love letters or philosophical reflections but itemised lists of debts owed, livestock pledged, barley allocated, and obligations yet unmet.

In other words, our entire linguistic evolution, our mythic Promethean spark of civilisation, didn’t ignite from the human desire to share stories or map the stars, but from a bureaucratic anxiety about who owed what to whom. That is more than anthropological trivia; it’s psychological DNA. The foundation of human economics, indeed of human record-keeping, is not barter, but credit. Not mutual aid, but institutional memory, often tinged with dread. Our earliest acts of inscription were not declarations of love or cosmic curiosity, but attempts to control, to track, to ensure that no favour went unpaid, no obligation unfulfilled. Debt is our original story… not the romantic kind, but the kind that bears interest.

And what’s most perverse, or perhaps just darkly elegant, is that this system of credit evolved not in isolated pockets but alongside, and often under the heel of, state violence. The temple recorded debts, and it extracted them. The king didn’t just invent coinage, he demanded taxes in it. Currency has always walked hand in hand with command. The moment money enters the scene, so too does someone who decides its worth, enforces its circulation, and profits from its scarcity. So the idea that money is a neutral medium, a value-agnostic facilitator of fair exchange, is not only naive but politically dangerous. It allows those in power to pretend they are simply managers of efficiency rather than architects of inequity. Behind every minted coin, there is a monarch’s face, a symbol of sovereignty, a stamp of ownership, not over wealth, but over people. And that legacy hasn’t evaporated; it’s simply migrated into sleeker disguises: the CEO’s salary, the algorithmic score, the bank’s interest rate.

Which brings us, reluctantly, to now, to this historical moment where money is everywhere and yet nowhere, where billions are created with keystrokes, and yet ordinary people are made to feel moral shame for overdrawing their checking accounts. And here’s where I’ll say it plainly: money today is not a thing – it is a promise, a claim, a delusion of liquidity propped up by trust in institutions that no longer seem trustworthy. Every dollar, euro, yen, or digital coin we transact with is not a token of inherent value but a soft, collective hallucination anchored in debt. Hyperbole?! Not at all. It is central bank policy. When you take out a loan, the bank doesn’t hand you someone else’s savings. It invents the money you now owe. You conjure your own shackles with your signature. What we call “credit” is merely sanctioned imagination, and yet we live in terror of it, entranced by it, judged by it, ruined by it.

And yet we still speak about money as though it were earned in the way fruit is harvested, as though it were the natural product of effort, discipline, and grit, rather than the ever-mutating consequence of access, inheritance, algorithmic chance, and geopolitical alignment. We still moralise the poor and sanctify the rich, pretending that financial solvency reflects ethical superiority rather than systemic entrenchment. We shame individuals for debt while sanctifying corporate bailouts. We treat poverty as pathology and wealth as virtue, even though both are often the result of inherited structure rather than personal merit. The myth of meritocracy survives because it flatters those on top and shames those below into silence. But make no mistake: money is not the harvest of virtue, it is the residue of power.

I’ve felt this tension inside my own life in ways I didn’t always have the vocabulary for. I’ve seen myself oscillate between disdain for money’s superficiality and desperation for its security. I’ve said things like “I don’t care about money”, while checking my balance before a grocery run, as if financial detachment were a luxury of the already padded. And worse, I’ve judged others for making compromises I have secretly considered (writing things I didn’t believe for people I didn’t respect, feigning excitement for projects that reeked of capitalist pageantry, smiling through the indignity of being underpaid because I was told it was “good exposure”).

It’s hard to talk about money without revealing what you’ve been willing to do for it – or against it. Behind every pay-check is a ledger of concessions, a quietly mourned version of yourself that didn’t speak up, didn’t say no, didn’t leave when the cost to your spirit was no longer worth the rent.

And of course, there is the global theatre of hypocrisy: the institutions that peddle austerity to the global South while laundering billions through loopholes in Luxembourg; the philanthropists who “donate” their wealth through tax-deductible foundations while gutting wages for their workers; the central banks that stoke inflation with quantitative easing and then scold citizens for buying coffee. We live in a world where economic advice is both weaponised and infantilising. Save more. Invest smarter. Buy less avocado toast. As if precarity were a budgeting problem, not a policy one. As if economic struggle were about personal failure rather than the rigged roulette of birth, class, and access. This isn’t a marketplace, it’s a maze designed to keep some running in circles while others fly overhead in private jets named after Greek goddesses.

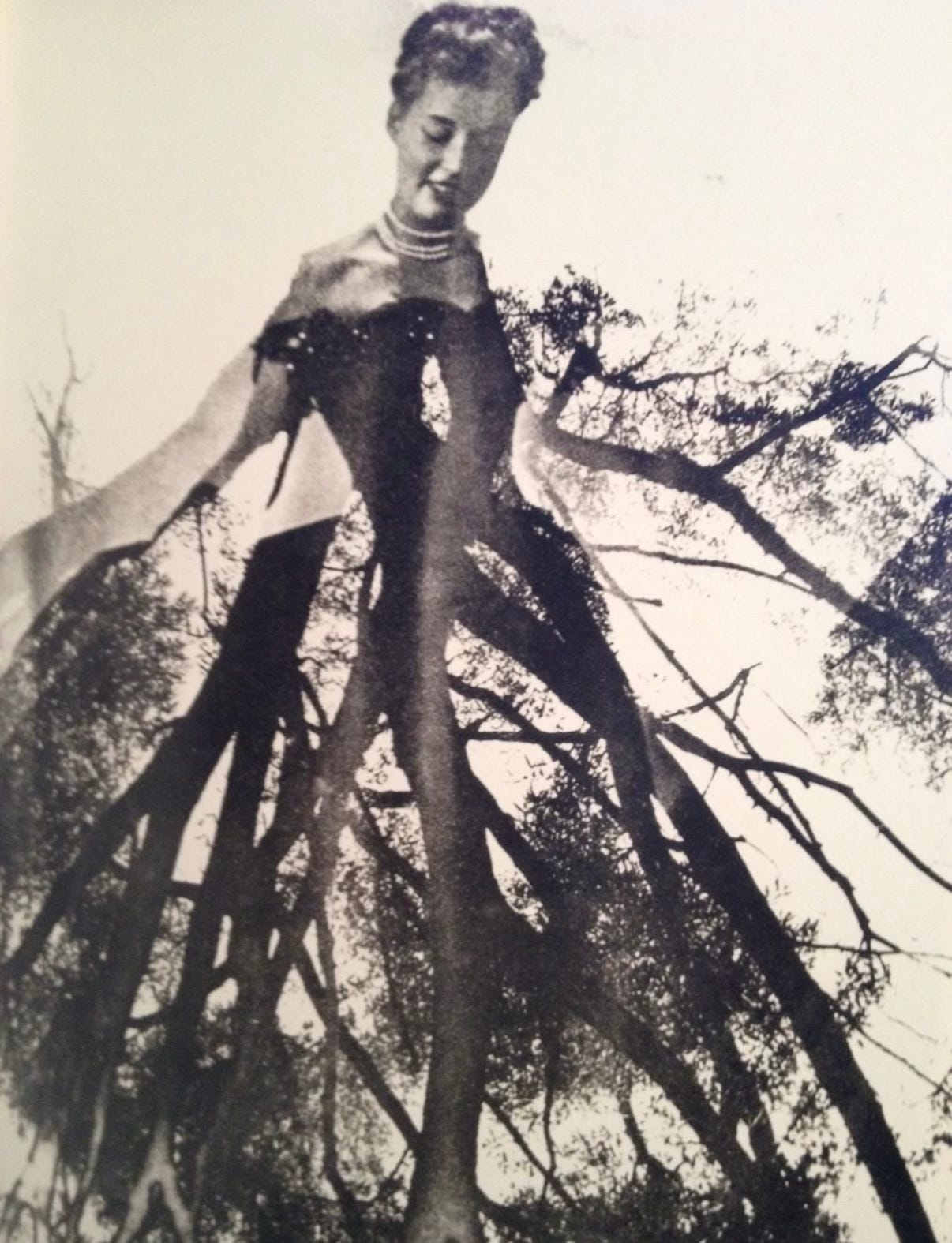

And here’s where the psychological damage creeps in… not just in the crushing anxiety of bills unpaid or the shame of asking for help, but in the way money shapes our imagination. It disciplines our desires. It makes us dream smaller. It turns artists into influencers, teachers into freelancers, and children into future entrepreneurs. It colonises our weekends with side hustles and poisons our sleep with passive income fantasies. We internalise the logic of monetisation so deeply that even our intimacy becomes performative: relationships as transactions, vulnerability as branding, selfhood as a portfolio of scalable traits. It is no longer enough to simply live, we must monetise our existence, or at least optimise it. Every moment must justify itself through metrics: likes, clicks, conversions, reach.

Even leisure must be productive.

Even grief must be content.

I know a woman who writes poetry so devastating it makes your throat ache. But she hasn’t published in years. “It doesn’t pay”, she told me. Instead, she ghostwrites LinkedIn posts for tech bros who call themselves thought leaders. Every month she invoices for thousands (her landlord’s applause, she jokes) but I can’t help but feel that we have lost something sacred. That somewhere between the ROI and the KPI, we forgot that some things are not supposed to be profitable. Some things lose their power the moment they are.

And yet, what choice is there? Poetry doesn’t pay the bills. Algorithms do. She knows it. I know it. And still, something in us mourns.

And this is where patronage matters. This is where we remember that while money may be tangled in systems of power, it can also be a conduit for possibility. Historically, the greatest works of art, literature, and music were not birthed in a vacuum of self-sufficiency. They were financed, supported, and protected by those with means – Medici families and eccentric salons, princely courts and modest benefactors. Patronage is not only philanthropy, it is cultural oxygen. And today, as platforms like Substack attempt to reimagine this model, we are being asked, again, to vote with our wallets. To say: this voice matters. This song matters. This novel, this painting, this slow essay that took a couple of weeks to write but will live in me for a year – it matters. Money, in these moments, becomes less about transaction and more about testimony. We pay artists not because they conform to markets, but because they remind us of what cannot be bought elsewhere. And when we do, when we choose to support creators whose work reshapes us, we are not simply funding their survival, we are preserving the soil of culture itself, before it is entirely paved over by corporate content farms and algorithmic drivel.

And what of the language we use to describe success? We don’t ask “Are you content?” We ask “Are you doing well?”… a question that has less to do with emotional stability or intellectual fulfilment than with monetary metrics. A six-figure salary. A home that appreciates in value. Assets. Revenue. Status symbols. We have become fluent in the dialect of capital, but illiterate in the language of meaning. We spend our youth chasing wealth, only to spend our wealth chasing back the years we lost to that pursuit. And when someone dares to opt out, to live slowly, modestly, unbranded, we call them naïve. As if wisdom were indexed to net worth. As if living softly in a brutal system were a form of ignorance rather than résistance.

The spiritual cost is harder to name, but it shows up in our exhaustion, our disconnection, our emptiness masked as productivity. We worship the market as if it were omniscient and omnipotent, even as it cannibalises the very things we claim to value: rest, beauty, sincerity, generosity. The invisible hand, it turns out, is often a pickpocket. And yet we defend the system, perhaps because critiquing it means acknowledging how thoroughly we’ve compromised. The greatest con of money might not be its structure, but how skilfully it recruits us into its logic. The genius of capitalism is not that it coerces obedience, it’s that it teaches us to brand our own compliance as ambition.

But…… and here I hesitate, because I don’t want to offer hope as an aesthetic gesture, there are moments, brief and trembling, when money does something else. When it becomes a means of trust rather than leverage, a gesture of care rather than control. When someone buys a meal they can barely afford because they want to honour a friendship. When someone donates anonymously, not for virtue signalling but because they remember what it felt like to need. These are not systemic victories; they are human ruptures within a dehumanised order. And though they don’t fix the machine, they remind us that the gears are not yet fully automated. That there’s flesh still caught in the cogs. That résistance, in this context, is not revolution but refusal to forget.

Once, someone paid me more than I asked for. “Your words changed something in me”, he said. That moment, absurdly small on paper, rearranged something in me. It made me realise that money is not always exploitation disguised as efficiency. Sometimes it is the only language we have to say, “You mattered to me.” And in a world where worth is constantly indexed to metrics, that soft human recognition matters more than the sum. It reminded me that value is not always measurable, and that payment, in rare and bright instances, can feel like reverence rather than remuneration.

So no, I’m not interested in dismantling the entire system tomorrow, nor in pretending that we can retreat into barter communes and blockchain utopias. What I’m saying is that money is not just an economic instrument, it is a narrative, a power structure, and a mirror of our most intimate contradictions. To talk about money is to talk about fear, longing, shame, trust, history, and the slippery algebra of who gets to live fully and who merely survives.

Let’s retire the story of the apple and the bread. Let’s stop pretending we are a society of traders negotiating fair deals and start reckoning with the truth: that we are participants in a system designed less for fairness than for control. That money, in all its sleek, digitised glory, is still haunted by the clay tablets that came before it. That it is, and has always been, a moral ledger dressed as math.

And yet, we still have the capacity to write differently on that ledger. To annotate it with generosity. To smudge its margins with ambiguity. To use money not as a measure of value, but as a way of noticing what we value most when no one is watching. We may not own the orchard. But sometimes, through patronage, through care, through the silent act of paying for something beautiful, we can choose whom we share the fruit with, and in doing so, nourish not just the artist, but the very possibility of a world where meaning is still allowed to matter.

With currency reimagined and value unconfessed, debtor to beauty, creditor to truth, from within the margins, generously smudged,

Tamara

One of the most brilliant essays I have ever read on Substack. Thank you, Tamara, for redefining so many concepts for us, from eroticism, to desire, to change, to attraction, fear, love, the body, the smile, privacy, men, intimacy, likability, disagreement, freedom…. and now money.

For those who haven’t explored your work the past six months, please, do yourselves a favor and get ready for a formidable ride.

You are one of a kind.

Tamara, this is excellent.

You managed to touch upon all of the misconceptions about money that most of us running the rat race haven't come close to gleaning: that all money is debt; that the barter system underpinning capitalist ideology is actually mythology; that money has become a means of measuring character; that the pursuit of money purely for its own sake is an endless treadmill; that the economic success we ascribe to hard work and an ascendency of character is, more often than not, merely the product of an inherited pole position, and ability to game the system; that nation building is as much about industriousness as it is about debt extraction from poorer nations forcibly backed into a geopolitical corner.

What's brilliant is that you take all of those insights, which are based on highly technical and often abstract evidence, and bring them into everyday life. Not merely to make them comprehensible, but relatable, and identifiable in everything from our choice to pay $4 extra for a cup of coffee, to the homes we choose to buy and the careers we pick to fund the entire mess.

Money isn't a harvest: it was invented precisely to solve the problems inherent to harvests; to create a store of excess value that wouldn't rot away uneaten and unused. As such, it creates two problems: that of abstraction, where money could be created separately from value, and that of exponential accrual, where certain circumstances allow for an owner or CEO to make a thousand times more than his employees, while convincing the world that he's bringing 1000 times the value.

None of this is to mention that you avoided the obvious pitfall of the capitalist/communist false dichotomy, and you make it clear that money is still important, still valuable, and, like any other instrument, can still be used for good. I could go on forever. A brilliant piece!