Home, Without Translation

Family closeness, inherited roles, tradition and the grief of self-editing

Some homes don’t shelter you. They remind you who you were before you learned to leave.

That sentence used to sound melodramatic to me, the kind of line you underline in someone else’s book and then silently mock while packing your suitcase. And yet, every December, as tickets are booked, inboxes fill with logistical tenderness (“What time do you land?” standing in for “Will you still be yourself when you arrive?”), and we rehearse the choreography of reunion, it returns with irritating accuracy. Not as philosophy. As muscle memory.

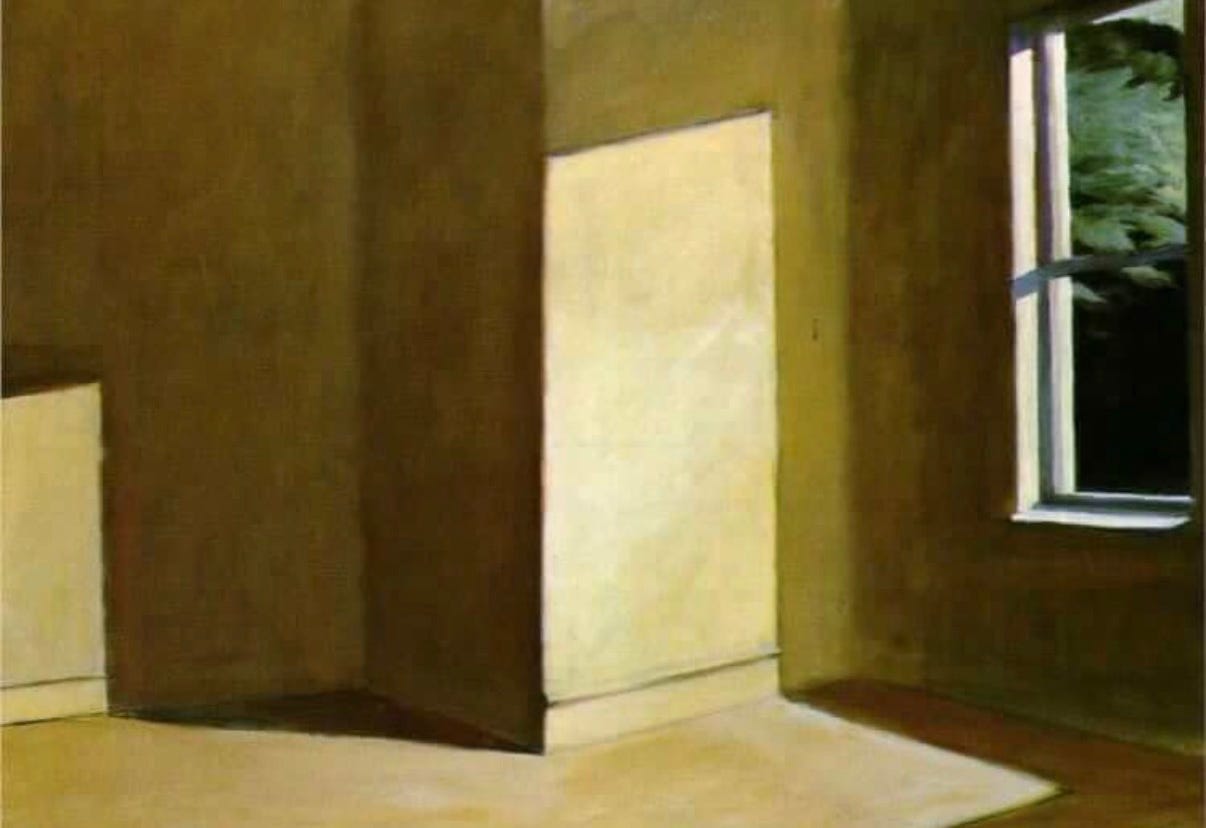

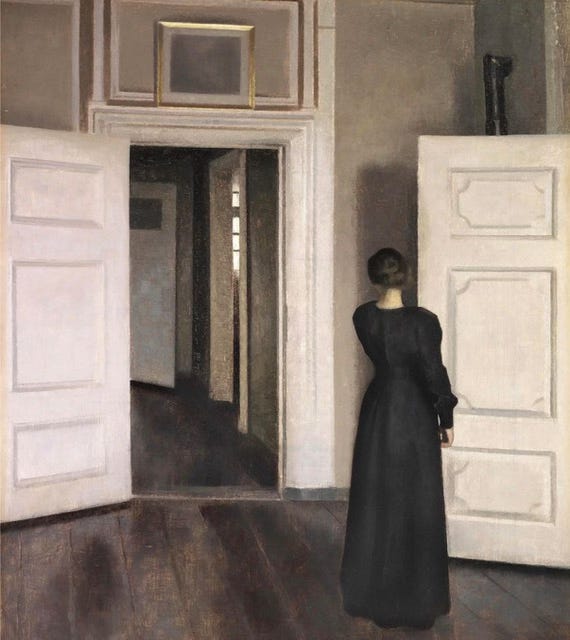

Home, in the seasonal imagination, is treated as a place you re-enter the way you re-enter a warm bath… with relief, recognition, softening. But many of us don’t walk into warmth. We walk into earlier drafts of ourselves, versions with fewer words, narrower permissions, clumsier desires. The door opens and the air shifts. Nothing dramatic happens, but everything familiar tacitly resumes its position. The tone. The jokes. The glances that land a half-second too late or too hard. You haven’t even taken your coat off and already your spine remembers how to brace.

This is rarely about cruelty. That would be easier. It’s about continuity. About the way family systems, particularly the wider, extended ones, preserve what once worked and keep serving it long after it’s gone stale. A role, once assigned, gains tenure. The sensitive one. The reliable one. The difficult one. The one who left and came back with opinions. You may have crossed borders, buried loves, learned restraint, lost illusions, found others. None of that necessarily registers.

At home, time doesn’t flow. It loops.

I notice it in myself before I can stop it, not with my parents (thank God!), but within the broader family machinery where habits outlive insight. My voice shifts. My sentences shorten. I explain things I would never explain elsewhere. I argue with a patience I don’t possess in any other setting, which feels virtuous until it feels faintly dishonest. Or I go quiet, which looks like maturity and functions like retreat. Neither option feels quite like me, and yet both are familiar enough to slip into without friction. That’s the danger. Regression that doesn’t announce itself as such. It just feels… efficient.

We tend to describe this as “going back”, but that gives it too much romance. Nothing actually moves backward. What happens is compression. The adult self, with its accrued nuance and hard-won ambivalence, gets squeezed into a shape that once made sense because it kept the peace or secured affection. You can still function inside it, just as you can still fit into an old coat if you don’t raise your arms. You just can’t move freely.

And then there are the traditions, which arrive with the moral authority of inheritance. The same meal. The same music. The same toast, told badly, retold worse. The same uncle repeating the same story, always reaching the punchline a beat too late, always pausing as if it were new. We praise these repetitions as intimacy, as though familiarity itself were proof of closeness, as though doing something together automatically meant touching one another in any meaningful way. It’s comforting to believe this. It saves time. It absolves us of the harder work: speaking plainly, asking questions whose answers might disturb the equilibrium, allowing ourselves to be seen as we are now rather than as we once were.

We mistake repetition for intimacy, and call it tradition.

Rituals, at their best, are containers for attention. At their laziest, they become substitutes for it. A full table can be crowded with avoidance. A house can ring with laughter and still feel oddly soundproof. Love circulates, yes, but it does so without friction, without conversation, without the small risks that signal presence rather than habit. The performance continues, smooth and polished, while something essential goes unaddressed because addressing it would require interrupting the script.

This is where the seasonal whiplash sets in. You are together and untouched. Surrounded and strangely alone. Fed and faintly starved. You participate because opting out would feel cruel or dramatic or ungrateful, words that carry more weight than they deserve, especially when spoken by people who haven’t examined them in decades. So you play along, telling yourself it’s only for a few days, that you can tolerate anything for a limited time, which is true in the way that running on a sprained ankle is true: possible, but mutely damaging.

I don’t want to pretend I stand outside this. I don’t. I love parts of these rituals. I miss them when they disappear. There is a particular smell that hits me when I walk into my family home, a mixture of citrus peel, overcooked sugar, cinnamon, and something indefinable, that still loosens a knot in my chest before I have time to think. Nostalgia isn’t fake. It’s just incomplete. It remembers selectively. It edits out the silences that followed the laughter, the conversations that never happened because no one knew how to begin them.

What complicates this further is the cultural insistence that family closeness is both natural and mandatory, a given rather than a relationship that also requires maintenance, negotiation, sometimes repair. Friends are allowed to evolve. Lovers are expected to be reassessed. Family, we are told, simply is. This belief grants enormous protection to patterns that would otherwise be questioned. If you feel unseen, you’re told to be patient. If you feel diminished, you’re advised to be grateful. If you feel yourself shrinking, you’re accused, implicitly or explicitly, of arrogance.

There’s a discreet moral economy at work here. Endurance is rewarded. Discomfort is reframed as loyalty. Growth, when it threatens the balance, is treated as a phase rather than a fact. You feel it physically before you can name it: the tight smile, the reflexive nod, the way your shoulders tense when a familiar topic approaches. And so the person who changes must either soften the change or carry it alone. Guess which option keeps the holidays pleasant.

Sometimes I think about this in terms of speech. What gets said. What doesn’t. The polite inquiries that skim the surface, the jokes that deflect, the shared memories that function as a kind of communal lullaby. Everyone knows the words. No one asks why the song hasn’t acquired new verses. Silence becomes tradition’s most faithful companion.

There was a year, I remember it with uncomfortable clarity, when I tried to break this rhythm. Nothing dramatic. I mentioned, casually, that I was tired in a way that sleep didn’t fix. That I felt unmoored. It wasn’t a confession so much as a temperature check. The room didn’t explode. It cooled. Someone changed the subject. Someone else poured more wine. Later, a relative took me aside and said, kindly, that maybe the holidays weren’t the right time for heaviness. As though there were a designated season for truth, and it wasn’t this one.

That was instructive. They weren’t wrong; timing does matter. But it clarified the terms. Togetherness here had conditions. Cheerfulness was currency. Vulnerability required pre-approval. I learned to file certain sentences away for safer rooms.

This is where humour sneaks in, uninvited but useful. There is something faintly absurd about the elaborate effort we invest in preserving atmospheres that no longer reflect us. We travel across continents to re-enact conversations we’ve already outgrown, like actors returning to a long-running play whose script hasn’t been revised since the first act yet still reviewed as “comforting”. The set is familiar. The cues reliable. The audience, ourselves included, applauds politely.

And yet. And yet….

It would be dishonest to frame this as a simple indictment of family or tradition. That type of clarity belongs to manifestos, not lived experience. What we’re dealing with is messier. Traditions can hold warmth even when they fail to hold us fully. Families can love sincerely and still lack the language for who we’ve become. There are gestures of care that don’t translate into understanding, and there is understanding that never quite makes it to the level of habit.

The tension settles exactly here, in that uneasy interval where the very structures that once buffered us from chaos, gave us shape, and taught us how to belong now struggle to hold the weight of who we’ve become without cracking, because any adjustment, however modest, however overdue, registers as a disturbance rather than a natural evolution. Stability, after all, is both their proudest achievement and their silent trap: it keeps things standing, legible, predictable, while simultaneously hardening the edges against anything that might require recalibration.

Change doesn’t arrive as curiosity in these systems; it shows up as a threat to internal logic, to the stories everyone has learned to tell themselves in order to keep going. And so, the system does what systems reliably do when faced with an anomaly… it closes ranks, smooths over the friction, explains it away, subtly pressures the deviation to settle down, tone it down, fit back in. The outlier is never expelled; that would be too obvious, too violent. Instead, they are coaxed, guilted, and gently worn down, until returning to an older shape starts to feel easier than holding ground, and accommodation passes itself off as harmony.

Leaving, then, isn’t something you can plot on a map or tick off once the suitcase is packed; it seeps in more silently, taking up residence in the mind long before the body follows, until one day you catch yourself hesitating, weighing whether it’s worth saying the thing you now know will land badly, and you realise the cost of belonging has always been paid in omissions. What once felt like tact begins to feel like self-betrayal, and the silences you learned to live with (because everyone around you insisted they were harmless, even necessary) start to weigh more than the comfort they bought. At that point, staying put means constantly biting your tongue, smoothing over edges, letting things slide for the sake of peace, and you can only do that for so long before something in you gives way. This isn’t a declaration of moral elevation, and it’s certainly not a badge of courage; it’s the dull, unglamorous recognition that the fit is off, that the arrangement no longer adds up, that you’re forcing yourself into a mould that has stopped giving. You haven’t outgrown people so much as outlived certain rules, and once you see that, there’s no unseeing it.

Incompatibility isn’t an insult, more like a fact of life, and learning to tell the difference between loyalty and self-erasure is less about walking out in a blaze of independence than about finally refusing to keep paying a price you can no longer afford.

I think of home now less as an origin point and more as an emotional climate. Some climates support certain forms of life and stunt others. You can survive in many conditions. Thriving is more selective. The mistake is assuming that endurance equals suitability.

During the holidays, this becomes stark. You arrive carrying new questions, new edges, and the old environment has no place to put them. So, they hover, awkward, making you restless. You go for long walks. You volunteer to run errands. You scroll your phone more than you like. You are not bored, but it offers a temporary exit ramp from a version of yourself you’ve been trying, unsuccessfully, not to reinhabit.

What’s rarely acknowledged is the grief braided through this process, not the one that demands casseroles or public language, but the procedural sort that files itself away in the background of daily life, showing up as fatigue, irritability, or a vague sense of being behind schedule with your own emotions. It’s grief for a home that existed more as a promise than a reality, one you kept returning to in the hope that this time the timing would be right, the adults more available, the atmosphere more generous, only to discover – again – that the conditions hadn’t changed and neither had the unspoken rules. It’s grief for the conversations that never happened because there was never a good moment, since someone was always tired, distracted, preoccupied, or because you learned early on that certain questions shut the room down faster than slamming a door. It’s grief for the fantasy that clarity would save you, that if you just found the right words, softened the tone, picked the perfect example, people would finally see you whole and respond in kind, rather than nod politely and carry on as before. And there’s a deeper, more destabilising grief beneath that: mourning the person you might have been had you not learned so young to read the room with forensic precision, to swallow reactions mid-rise, to become fluent in self-editing as a survival skill. That loss doesn’t announce itself as tragedy; it creeps in sideways, through envy of people who seem unburdened by second-guessing, through a sudden ache when someone offers you ease you didn’t know was possible, through the realisation that parts of you were trained to lie low after the danger had passed.

I don’t write this from a place of resolution. I still go. I still sit at the table. I still participate, sometimes wholeheartedly, sometimes with a private sense of doubleness that I don’t bother to resolve. I’ve stopped expecting the setting to transform simply because I have. That expectation was a form of arrogance disguised as hope.

What has shifted, almost without announcement, is my sense of obligation. Not the logistical one, that remains, but the emotional one. I no longer feel compelled to compress myself for the sake of harmony. If I grow quieter, it’s because I choose to listen. If I leave the room, it’s because I need air. If I decline to perform cheer, it’s because neutrality is truer in that moment. These are small acts. They don’t announce themselves. They don’t fix anything. But they keep me intact.

There’s a peculiar relief in admitting that some forms of closeness have limits. That intimacy cannot be summoned by repetition alone. That love without conversation has a shelf life, even when it continues out of habit. Naming this doesn’t destroy tradition. It clarifies it. It allows you to see what is being offered, and what is not, without the pressure to pretend otherwise.

Hope lives here, if anywhere. Not in the fantasy of a perfectly attuned family gathering, but in the possibility of creating pockets of honesty within imperfect structures. A conversation taken outside. A boundary held without explanation. A tradition gently declined. A new one, tentative and unremarkable, introduced without ceremony. These gestures won’t trend. They won’t photograph well. They might even go unnoticed. That’s fine.

Home, I’m learning, has far less to do with return than with recognition, with that almost elusive moment when you realise you do not rehearse, soften, or run an internal subtitles track to make yourself legible to the room. Home is the difference between being asked how you are and having the answer actually land, between speaking in full sentences and watching someone stay with you long enough for the meaning to catch up. Sometimes this recognition happens with friends who let conversations sprawl and circle back without demanding conclusions, or with a lover who doesn’t flinch when your mood shifts one evening and doesn’t need you to tidy it up for their comfort. Sometimes it happens in a city that allows you to walk anonymously for hours, where no one expects continuity from you and the streets don’t carry your childhood footsteps, or in solitary routines (early mornings, repetitive swims, long bike rides) where no one is monitoring who you’re supposed to be and you can finally drop the performance without commentary.

And sometimes, more unsettlingly, it doesn’t happen anywhere for long, which forces you to sit with the unnerving truth that home may not be a stable location but a temporary alignment, something you pass through rather than settle into. That uncertainty has teeth; it strips away the reassuring fiction that belonging is guaranteed if you just try harder or wait patiently enough. But it also signals adulthood in its most unglamorous form: the acceptance that recognition must be negotiated, not inherited, and that learning to live without a permanent landing spot is, for better or worse, part of taking responsibility for who you’ve become.

There is, of course, another version of home that rarely gets admitted into these conversations without tipping into cliché, and so we tend to exile it from serious reflection, even though it may be the most accurate one: home as another person. Not the fantasy of fusion, not the romantic shorthand of being “completed”, but the more exact experience of recognition that happens in the presence of someone who does not require you to shrink, translate, or manage yourself into legibility. This kind of home is not inherited; it is encountered. It doesn’t arrive through obligation or repetition, but through attention, through the rare and almost disarming relief of being received without negotiation. With the right person, your sentences don’t trail off in self-censorship, your moods aren’t treated as inconveniences to be corrected, and your silences don’t trigger alarm or abandonment. Their arms feel like home, they protect you from the world and allow you to remain intact inside it. This is recognition in its most embodied form: being seen without being reduced, adored without being curated, met without being managed. It is not permanent, not guaranteed, and not immune to failure, but when it exists, even briefly, it recalibrates your understanding of belonging altogether. After that, returning to spaces where love requires performance feels unmistakably like exile, because once you’ve known what it is to be at home in another’s regard, everything else reveals itself for what it is: shelter, perhaps, but not refuge.

As for the old homes, the ones that shaped you and still claim you, perhaps the most honest stance is gratitude without amnesia. Affection without self-erasure. Presence without performance. And when that balance fails – and it will – permission to step outside, breathe, and remember that leaving once taught you something essential.

Not how to abandon.

How to survive with your edges intact.

That, for now, is enough.

Written from a place where I am still learning to stay whole without rehearsal or translation,

Tamara

I have the same feeling every time I read a Museguided essay: watching someone slowly, patiently lift the velvet curtain on a mechanism we all know is there but rarely examine so closely. This essay reminds me of “Blue Valentine”, because it understands how intimacy fossilizes when it’s treated as static rather than responsive. In that film, shared history becomes a script people keep replaying long after it stops reflecting who they are. The emotional harm isn’t driven by cruelty or spectacle, but by a failure to revise the terms of closeness as the people inside it evolve. The looping between past and present mirrors your line, “At home, time doesn’t flow. It loops.” In both, love persists while recognition fails.

I love how you frame regression as efficiency. That idea feels important and under-explored, how self-editing becomes seductive precisely because it works, because it keeps the machinery running smoothly even as it extracts a long-term cost. It made me wonder whether part of the grief you describe isn’t only about what was lost, but about how competent we became at surviving these climates. There’s a skill there—reading rooms, smoothing edges, timing truths—and perhaps another layer of your essay could explore what it takes to unlearn a competence that was once necessary. Not just leaving home, but relearning how to take up space without scanning for consequences.

The way you frame your ideas is remarkably disciplined. But by now all your readers are used to that. The sentences breathe, the metaphors never announce themselves too loudly, and the thinking unfolds without forcing a conclusion. I especially admired your refusal to manufacture villains. There’s no cruelty here, just systems doing what systems do, and that restraint is what gives the essay its authority. Like the film it echoes for me, the pain is small, procedural, almost polite, which makes it far more unsettling than any overt rupture.

There’s a generosity in this writing that doesn’t dilute its clarity. You hold affection and disillusionment in the same frame without resolving them prematurely, which feels deeply honest. You don’t tell the reader what to do; you teach us how to see. And once you see it, the compression, the looping time, the cost of “pleasantness”, it’s very hard to unsee.

Dear Tamara, thank you for writing something so many of us carry in our bodies without daring to speak of. It feels less like being persuaded, and more like being recognized, which you always do perfectly.

This is extraordinary because of how precisely you name the mechanics of erasure. The line “At home, time doesn’t flow. It loops.” is doing serious intellectual work; it captures something anthropologists, therapists, and novelists circle for years. You’re describing systems memory, the way families across cultures preserve identity by freezing people in legible roles. Whether it’s the eldest son in a Confucian household, the dutiful daughter in Mediterranean families, or the “one who left” in immigrant lineages everywhere, the pattern is universal: continuity is valued over truth because continuity feels like survival.

I love your distinction between ritual as attention and ritual as avoidance. That reframes tradition as active or inert, far from good or bad. It explains why the same table can feel nourishing in one culture and suffocating in another, and why the feeling can flip within the same family across time. I also love that you say that self-editing begins as love and ends as habit. No villain required.

I admire how you refuse both the easy indictment and the sentimental rescue fantasy. The essay stays adult. It acknowledges that belonging has a cost structure, and that at some point the interest compounds faster than the warmth. You show zero bitterness and I admire that even more.

This feels like a piece about migration that never names geography: the migration from inherited meaning to negotiated meaning, from scripted belonging to earned recognition. Every culture has a word for “home”, but very few have language for when home stops updating its software as Alexander write. You’ve given us that language.

Tamara, thank you for writing something that doesn’t demand rupture, only clarity. It makes me wonder how many of us are grieving the loss of permission to speak in full sentences inside a home?