Flirting With the Future

Against control: toward a more erotic theory of change

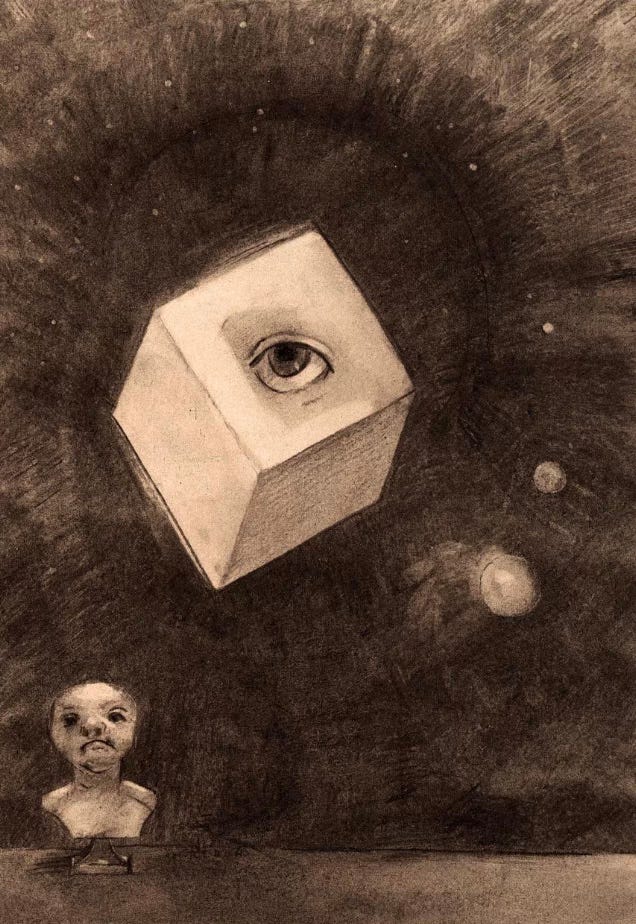

There are days, and I suspect you know this too, though perhaps you phrase it differently when you whisper it to yourself before sleep, when the future feels less like a horizon to walk toward and more like a person observing you from across a room, inscrutable and a little amused, as if it already knows what version of you you will become long before you have learned how to articulate even the first syllable of that transformation.

And on those days, when the air is thick with the hum of possibility and dread braided so tightly you cannot tell which strand you’re tugging at, I find myself wondering whether we, in our frenetic, overarchitected, spiritually dehydrated modernity, have misunderstood entirely the nature of that gaze; whether we have attempted to treat the future as a stubborn bureaucratic document requiring signatures and conditions rather than as a creature whose language resembles seduction more than planning, flirtation more than control, the charged dance of the almost-happening rather than the grim discipline of what absolutely must.

Because if I am honest, there has never been a single moment of genuine change in my life that arrived because I scheduled it into being, narrated it to the universe with the blind confidence of someone who believes desire can be domesticated into a spreadsheet, or manifested it through a regime of affirmations that sound, in retrospect, like a hostage reading lines at gunpoint. No, the moments that undid me, reshaped me, seduced me into versions of myself I had not yet earned, those moments entered like a stranger’s smile viewed sidelong on a train platform, a brief and devastating flicker that rearranges the interior climate of your thoughts. They did not come when I was disciplined; they came when I was pervious.

And yet, perversely, we have built a culture that fears receptivity as if it were a moral failure.

Certainty has become the new virtue, control the new sacrament.

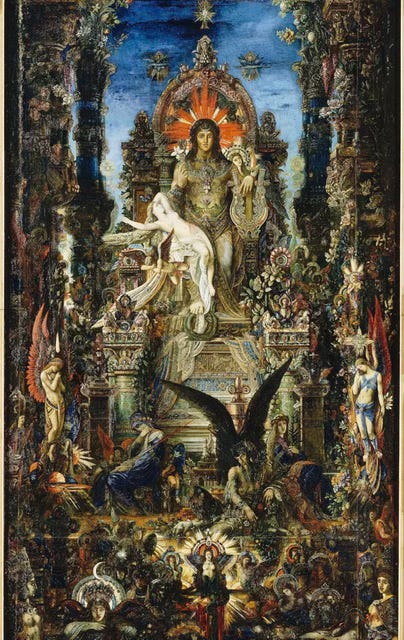

People talk about “manifesting” the way medieval mystics talked about revelation, except now the ecstatic encounter has been replaced by the instructional video. It is a strange spiritual impoverishment: the belief that the future needs to be bullied into compliance, forced into linearity, or, perhaps even worse, cajoled into materialising exactly what we think we want, as though what we think we want is not, nine times out of ten, the shallowest interpretation of a deeper longing we have not yet found the courage to name.

It is here that I begin to suspect that the future, like any sophisticated interlocutor, resists coercion. It prefers suggestion. Future opens under the pressure of curiosity, not conquest. And if this sounds suspiciously like seduction, good! It should. Seduction, the real one, not the performative manipulative simulacrum that pop psychology insists on diagnosing, is nothing more or less than the art of creating a charged space between the known and the possible. It is an invitation to reciprocity. A trembling corridor of potential. Those who understand seduction understand time: the way the not-yet pulses through the present, drawing us forward, requiring a specific blend of attention and surrender that control simply cannot fathom.

The future, in other words, is flirtatious by nature. And we, in our quant-obsessed, algorithm-chained, hyper-rationalised age, have forgotten how to flirt back.

Not in the cheap, winking, pick-me sense – no! Flirtation, properly understood, is a form of epistemology. It is how the psyche investigates the unknown without collapsing under the weight of expectation. It is how one approaches what might be, with an awareness that this might is, in itself, sacred. Because flirtation thrives in uncertainty; it is a ritualised reverence for ambiguity, a refusal to demand premature clarity from what is still becoming.

And perhaps this is why so many people feel chronically unfulfilled even when they achieve the things they once declared non-negotiable: goals achieved without flirtation are sterile. They leave no aftertaste. They move you linearly but not deeply. They lack the eroticism of the unforeseeable, the vertigo of an unplanned possibility brushing against your life and altering its temperature.

When I think of the decisions that shaped my adult life, they have the texture of flirtation, not certainty. Paris, after all, flirted first, when I was fourteen and arrived for the first time to a city that seemed to recognise me before I had even begun to recognise myself, a city that brushed past my shoulder with the effortless arrogance of someone who knows they will be remembered. I wrote about this in a short story that remains very close to my heart, My Most Arduous Lover. And then, years later, at twenty-two, I obeyed that early shimmer and moved there, only to flee again when life’s centrifugal forces spun me outward before I could learn how to stay; yet the imprint lingered, the way an unfinished conversation lingers in the body long after the words dissolve.

So, when I moved back to Paris, the last return, the irreversible one, I did not do it because I had a well-defined plan or because I solved for variables the way consultants do when they attempt to tame reality through PowerPoint. I moved because that same strange internal shimmer insisted, once again, on being acknowledged. It was not reason; it was not logic; it was a seduction that had been waiting patiently for me to grow into it. Paris had leaned in long before I knew how to respond, and when I finally did, I realised something that should have been obvious but is only obvious in hindsight: the future belongs to those who recognise when life is leaning toward them.

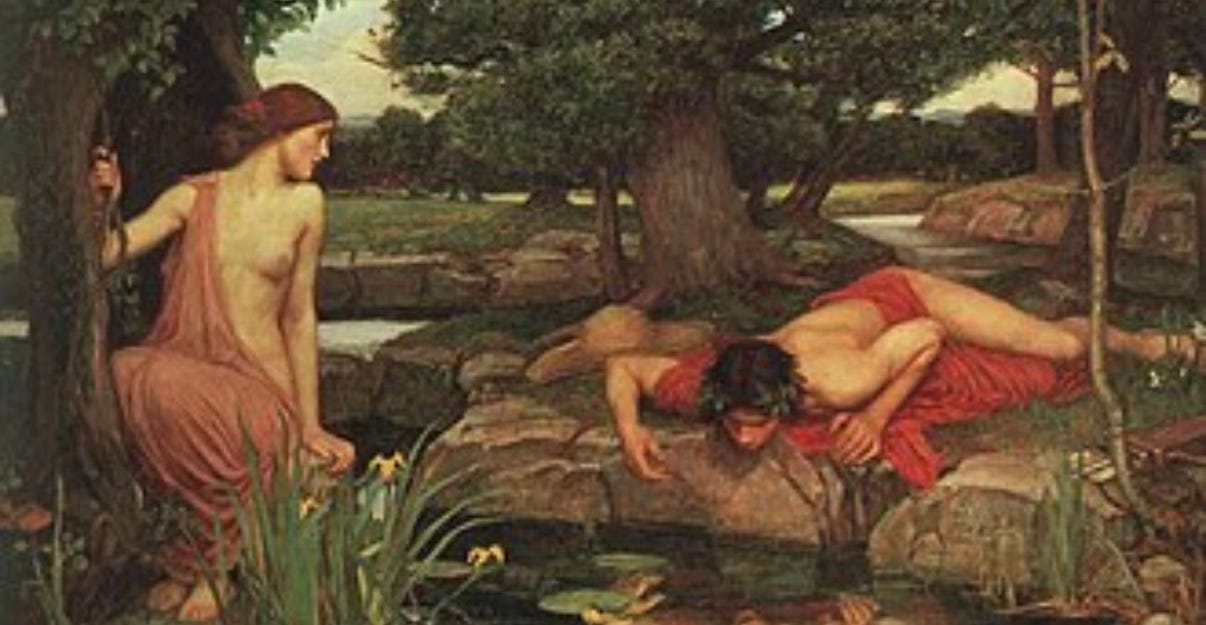

Most people don’t recognise it. They are too busy negotiating with the universe, too anxious to notice the subtle shift in atmospheric pressure that precedes a revelation, too terrified of uncertainty to allow it to become erotic. But uncertainty has always been erotic. The Greeks knew this, they wrapped entire cosmologies around the idea that fate is a trickster, a shapeshifter, a visitor arriving in disguise. Hermes, that divine smuggler of transitions, did not deliver the future on a schedule; he arrived laughing, carrying messages that destabilised more than they reassured. To flirt with the future is to accept Hermes as one of your gods.

But let me descend from myth into the near-scandalous practicality of the everyday because despite what productivity evangelists insist upon in their dopamine-coloured bullet journals, flirtation is far more efficient than discipline at generating meaningful change.

A flirtatious mind, neurologically speaking, is alert without being rigid; it is attuned to pattern but not enslaved by prediction. It can pivot. It can notice. It can play. And play, though the corporate world despises the term unless it is used to describe a networking golf event, is the neurological state in which creativity thrives. Flirtation expands your perceptual bandwidth. It softens the obsessive loops of fear. It makes space for improvisation.

Which is why, though it embarrasses the disciplined part of me to admit it, everything I’ve written that truly mattered came not through effort but invitation. The good sentences, the ones that startled me with their accuracy, the ones I felt embarrassed to publish because they revealed more than I intended, those sentences arrived unannounced, like someone slipping into a room whose door I had forgotten to latch. They emerged from the logic of flirtation: an idea hovering, circling, waiting to see whether I was paying attention. And if you want to know what it costs to let sentences arrive this way, uninvited, unfiltered, and uncomfortably honest, you might find your answer in one of my rawest and most personal essays, the one I called The Sentences That Would Ruin Me.

Here is the uncomfortable truth: the future behaves exactly the same way. Whenever I attempted to control it, to force clarity, to clutch at outcomes, to demand certainty the way a child demands sweets, life grew quiet, as if offended by my lack of imagination. But whenever I adopted the posture of flirtation, a curiosity sharpened by self-respect, an openness laced with independence, something shifted. A door cracked open. A person appeared who changed my life forever. A phrase arrived that led to an essay I had not known I was capable of writing.

Why, then, do we persist in treating the future as a problem to solve rather than a partner to seduce?

Part of it, I suspect, is cultural. We have been marinated in an ideology that equates control with competence, predictability with virtue, discipline with moral superiority. The self-help industry has turned the future into a battleground where the only acceptable victory is mastery. The corporate world has colonised imagination and rebranded it as “vision”. The algorithmic age wants us to believe that if we can just quantify enough variables, uncertainty will kneel obediently.

But this worldview is spiritually, intellectually, and erotically bankrupt. It leaves no room for the intelligence of desire, the improvisational genius of coincidence, the strange but reliable choreography of events that unfold only when we stop suffocating them with intention.

I sometimes think that the world would be kinder, or at least more interesting, if we replaced the language of goal setting with a language of seduction. Not the sterile “What are your objectives?” demanded by performance reviews and productivity gospel, but questions that move with a different grammar of desire… “What draws you? What pulls you across the room? What creates that internal lift, however irrational, that makes your breath rearrange itself just slightly?”, questions that would allow a person to admit, perhaps for the first time, that the most decisive turns in their lives were seldom the result of strategy and far more often the consequence of a gravitational tug they couldn’t justify.

Imagine asking a young doctor not why she chose cardiology but when she first felt her pulse quicken in a lecture hall from recognition; imagine inviting a would-be architect to speak not about job security but about that childhood moment when he stood beneath a cathedral vault and realised that space itself could teach a person how to breathe; imagine encouraging a man in midlife, terrified he is running out of time, to confess that the book he dreams of writing keeps whispering to him in the shower, in line at the grocery store, in the liminal hour between exhaustion and sleep because it wants him.

Imagine career counselling conducted like a late-night conversation between conspirators, evaluating impulses not KPIs. Imagine spiritual practice as an erotic dialogue with what might be, a willingness to approach the unknown without pre-emptively baptising it as either miracle or catastrophe, not as a quest for transcendence. Imagine ambition that does not grind but glimmers.

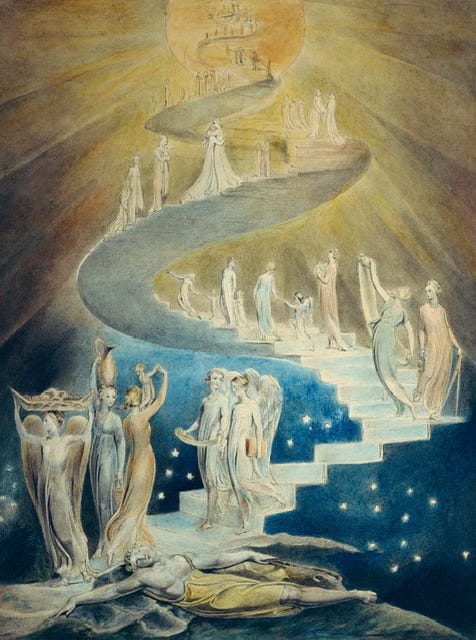

We might, in such a world, become people who choose paths because they are alive; people who follow the shimmer instead of the script; people who understand that what changes us rarely announces itself in the language of plans, but in the sensation of being quietly summoned.

Ambition, stripped of coercion, is just desire with endurance. And desire, when treated with respect rather than shame, becomes a navigation system. Yes, desire misleads sometimes. So do maps. So do mentors. So do algorithms. At least desire has the decency to be alive.

There was a year, not long ago, when I tried to control everything. I wasn’t greedy, but I had a lot of fears. I told myself it was maturity, professionalism, the noble discipline of someone finally taking herself seriously. But the truth was uglier, I was terrified that the ground beneath my life was dissolving and I wanted a future that behaved like a loyal dog, obeying every command. And in that year, the worst year for my creativity, nothing worked. Everything stalled. Possibilities dried up. Connections thinned. It was as though life itself had stepped back, waiting for me to stop issuing demands like a petty tyrant who had mistaken her anxiety for authority.

Only when I loosened my grip, not released it entirely, but loosened it the way one loosens their posture at a dinner where someone interesting has just entered, only then did something stir. I did not manifest anything; I allowed something. I flirted, timidly at first, with the unknown. And the unknown, recognising its cue, shifted closer.

This is, I think, the secret few dare to admit: the future does not respond to excellence; it responds to availability. Not the desperate availability of someone begging for a sign, but the autonomous availability of someone who is willing to be changed.

Which is also, if we are honest, the foundation of all romance.

It is impossible to flirt meaningfully if you are terrified of losing control. Flirtation requires vulnerability. And I’m not talking about the performative, teary-eyed Instagram variety, but about the discreet, unmarketable kind that says: I am here, not knowing what will happen, willing to move toward something that might undo me or reveal me or expand me or require me. It is the vulnerability of approach.

And approach is the essence of becoming.

There is, of course, a risk in this way of living. Flirtation with the future does not guarantee reciprocation. Sometimes you lean toward a possibility, and it dissolves. Sometimes the thing that shimmered was only a mirage. Sometimes you misread the cues. You were not foolish but life, like any worthy partner, has moods. And yet I cannot help believing that these disappointments, though painful, are instructive. They refine discernment. They train intuition. They reveal where your desire was genuine and where it was merely a performance of wanting.

Failure, in flirtation and in futurity, is a form of calibration.

But the greatest risk, I think, is not that flirtation fails; it is that control succeeds. Flirtation at least grants you the dignity of revelation, you learn what stirs you, what frightens you, what expands your breath or compresses it, what possibilities quicken as you lean toward them and which ones recede the moment you try to claim them. But control, when it triumphs, is a far more insidious conqueror: it may grant you the life you petitioned for, the tidy constellation of outcomes you once believed would secure your happiness, yet it will deny you the life that might have astonished you, the life that would have startled you awake at 2 a.m. with the intoxicating sense that you had not merely followed a path but answered a call.

Control delivers its victories like pre-packaged predictable, nutritionally adequate, spiritually anaemic meals, while flirtation offers the unpredictable feast, the dish you did not know you loved until it was already dissolving on your tongue. And though people claim to want certainty, what their interior worlds crave, secretly, hungrily, is interruption: the encounter that reroutes them, the coincidence that refuses to behave like chance, the invitation they would never have dared to write into a five-year plan but that nevertheless arrives, shimmering with the unmistakable voltage of the unforeseen.

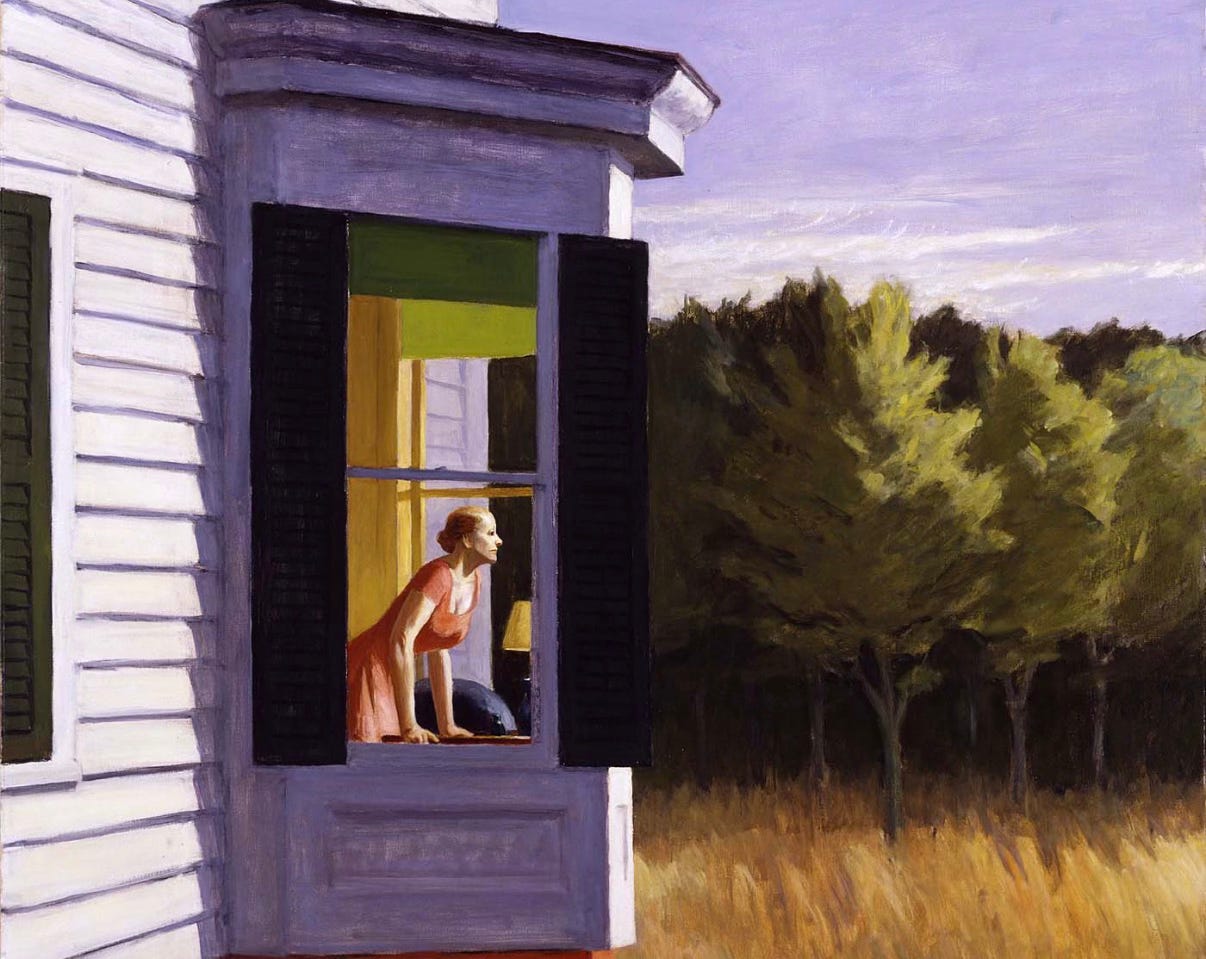

The true tragedy, then, is not unrequited flirtation; it is living in a fortress you mistake for a palace, congratulating yourself on your discipline while the unlived versions of your life gather outside, like patient, disappointed lovers, wondering why you never came to the window.

Because the future, the real future, the one that changes you, does not enter through locked doors. It waits for a crack, a gesture, a surrender so small it feels like nothing at all, and yet that tiny gesture is the hinge upon which entire eras of your becoming could turn.

Which brings me to the inconvenient confession that this entire essay has been circling, though I attempted, at moments, to dodge it with theory: I want to flirt with my own life more. I want to approach the future as a presence with its own will, its own tempo, its own appetite for reciprocity, not as a sequence of tasks requiring my managerial oversight. I want to be surprised again, not by catastrophe, but by possibility. I want to feel that internal lift, that shimmer of what-could-be, and instead of interrogating it to death, I want to take one step closer.

And perhaps, though I am cautious even about this, perhaps I want the future to flirt back.

Not with guarantees. Not with a neatly resolved narrative arc. Not with some algorithmically satisfying manifestation of my best self. No! I want something messier, more human, more aligned with the ancient truth that becoming is less about destination than orientation.

I do not know what will happen. I no longer trust people who pretend they do, the prophets of certainty, the spreadsheet mystics, the vision-board evangelists who speak of the future as if it were an obedient apprentice rather than a mercurial sovereign. Life has corrected me too many times, often with the precision of a well-aimed slap, for me to maintain faith in anyone who claims mastery over the unfolding. But I do know this: the only times I have truly lived (not performed life, not managed it, not narrated it into something respectable) were the moments when I allowed myself to be lured, drawn toward something whose logic I could not articulate but whose pull I felt unmistakably in the body.

A city once lured me, first when I was a teenager and Paris brushed past me like a man who knew he would return later, and then again in adulthood, when its presence rekindled something I had nearly trained myself out of wanting. A person lured me recently, and if I am honest, with that devastating charm of someone who becomes a hinge in your emotional frame without ever announcing their arrival. Sometimes it was an idea that beckoned, sidling into my mind with the seduction of a secret I had not yet earned. And sometimes it was nothing more than a sentence, a single, unassuming line that detonated inside my chest and rearranged my thoughts. These were the moments that left marks. These were the moments that felt like living rather than simply continuing.

And it seems to me, with the type of intuition that refuses to submit to rational audit, that the future behaves in much the same way. It watches us, perhaps, from across whatever metaphysical room separates the not-yet from the now, assessing not our qualifications or our discipline or the grim determination with which we insist we are “ready” but our softness, our permeability, our willingness to tilt our attention toward what shimmers instead of what is safe. If the future is flirting, and some days I feel this with a clarity that startles me, then aliveness becomes a matter of flirtation as well: the art of signalling interest without demanding outcome, of leaning forward just enough for possibility to recognise itself in us.

Because maybe aliveness has never been about intensity or novelty or even courage in the heroic sense; maybe it is about the subtler capacity to remain seducible. To resist the deadening cynicism that adulthood tries to install like a mandatory software update. To keep, against all cultural instruction, a part of the psyche unarmoured, still capable of being surprised, still willing to be undone by the arrival of something unexpected. There is a terrifying tenderness in that posture, and yet, I suspect, it is the only one that allows the future to draw near without recoiling.

If the future is watching, and I have felt its gaze often enough to believe it is, then it is not looking for the most prepared among us, but the most responsive. The ones whose eyes can still soften, even after disappointment; the ones who know that desire is a compass, not a liability; the ones who understand that flirting with what might be is the earliest gesture of becoming who we are not yet. And perhaps that is the subversive truth under all of this: that the future chooses only those who are still willing to be chosen.

Not to conquer. Not to manifest. Not to demand. But to flirt.

To lean. To notice. To risk approach.

Perhaps that is enough, or perhaps it is only the beginning of enough, the embryonic form of a relationship with time that does not require domination to feel meaningful. Because there is a strange dignity in choosing responsiveness over strategy, in allowing the world to meet you halfway rather than forcing it to kneel at your blueprint. It is a way of living that honours intelligence without strangling spontaneity, a way of signalling that you are available to the unknown without abdicating your agency within it.

And if it isn’t enough, if the future remains coy, if possibility delays its entrance, if uncertainty continues to hum with its maddening, erotic indifference, then at least I will know I did not live my life as a project manager of fate, but as its co-conspirator. Someone who extended a hand to the unseen. And I didn’t expect it to grasp mine, but the gesture itself felt like a form of allegiance to the better parts of my nature. Someone who chose curiosity over choreography. Someone who understood that the meaning of a life is rarely found in the moments that obeyed the plan, but in the unanticipated invitations that asked for a courage I did not know I possessed until I gave it.

There is a difference. The world feels different when you stop interrogating it and start listening for the seductions beneath its noise. You become different, not more powerful, perhaps, but more receptive to wonder, more attuned to the faint shimmer at the edges of possibility, more willing to be altered by what you cannot yet name. You begin to sense that the future is not a static destination but a living conversation, one that requires your participation, your attention, your willingness to be surprised.

And in that difference, a kind of hope that is not triumphant or naïve, but qualified, the only one worth keeping, begins to glow. A hope that does not promise reward but invites alignment. A hope that understands that life, when approached with the reverence of a flirtation rather than the rigidity of a plan, becomes less something to control and more something to collaborate with. A hope that is not loud or evangelical, but persistent and strangely faithful, a hope that remains even when certainty does not.

Perhaps the future has never wanted obedience or strategy or immaculate preparedness from us, only the willingness to lean a little closer when it winks.

In devotion to the shimmer at the edge of the almost-happening, with a heat still tilted toward the mysterious intelligence to the unknown, and a willingness to move closer whenever the future winks,

Tamara

There is a great misconception that the strongest survive, when that's never been the case. It's not strength, but adaptability that wins, because even the most rigid, load-bearing material eventually snaps under enough pressure. It's the same with control, where the desire to exert control itself eventually erodes your ability to maintain it. If you're driving over black ice, the strength of your grip on the wheel does not stop the car from spinning; rather, it's your ability to turn with the skid that allows you to maintain control. And that requires having a loose enough grip to turn reactively.

The desire for control is half of the survival equation; the other half is the chaos that impinges itself on our lives. The struggle to make order out of chaos has to be calibrated. In other words, control is adaptive when our desire for control matches the chaos we're confronted with. In life or death situations, the drive to control will save your life; it's useful as a reaction to circumstances. The problem with the future is that you can't be reactive to something that hasn't happened yet, hence why openness to experience and possibility - what you call flirtation - is the best way to prepare yourself for it. Control doesn't work, because it treats the future like a multiple choice question where there is only one right answer or path, instead of seeing all of the possibility of optional paths.

This is the reason why all of the great change in our lives happens when we flirt with the future; when we relinquish control. We loosen our grip on the wheel and become dynamic in our ability to both see and react to the different possibilities, as opposed to trying to force our lives down one narrow path, only to find that the road has long been closed.

Always insightful, always incisive, and always intuitive. Thank you, Tamara.

I’ve read this and entered in a secret chest in my mind where I’ve been stockpiling all the moments I pretended were “accidents” instead of invitations.

Honestly, the times my life has actually pivoted have never come from the versions of me gripping a to-do list like a life raft but from the little breaches in my self-management. The night I missed the last train and ended up walking home with a stranger who became a lifelong friend. The time I said ‘yes’ to a job I wasn’t “strategically aligned” for, simply because something in me leaned toward the unknown heat of it. Or the moment I caught myself grinning at a future as if it had just whispered something obscene and promising in my ear.

Control never gave me that. Control gave me a year that looked impressive on paper and felt like eating unseasoned oatmeal in the dark. Horrible, I know.

What you write about flirtation feels uncomfortably accurate. The future has always shown up for me in the same way people do when they’re genuinely interested, that is slantwise, playful, completely indifferent to my plans. And every time I tried to behave like a responsible adult and “optimize” myself into transformation, life stopped flirting back. I’ve never felt more invisible than when I was trying to be impressive. I can’t even believe I’m writing this here. But it’s true.

Lately, I’ve been practicing what you describe, that subtle tilt of attention, noticing what sparks without trying to own it, letting tiny, irrational curiosities tug at me. And the wildest thing is that it works. Not like magic. Obviously! More like gravity rediscovered.

Your essay is the permission to admit that maybe the most grown-up thing any of us can do is to stay seducible. To stay interruptible. To stay willing, because every time I’ve been bold enough to follow the shimmer instead of the checklist, my life stopped behaving like an obligation and started behaving like a conversation I actually wanted to have.

And maybe that’s the whole secret that you’ve just generously shared with your readers, the future answers only when we stop talking at it and start flirting back.

Tamara, this is everything I needed to read as another year finishes soon.