Change, the Most Honest Violence

On the messy, merciless truth of the unmarketable, unmapped, and unfinished work of transformation

Change is not a butterfly. It is not a rising sun, nor a phoenix ash-dusted in self-help slogans or the favourite metaphor of a TED Talk speaker in transitional career pants. Real change, the kind that ruptures, disorients, and forces a reckoning so unceremoniously intimate it feels surgical, rarely announces itself with flourish. It begins quietly, sometimes in the bored fatigue of repetition, sometimes in the blinding nausea of betrayal, but always in the moment when the story you have been telling yourself about yourself no longer fits your body. Change is the moment when narrative outgrows identity, when who you are begins to rot inside who you were, and there is no ceremony, no audience, no applause, only the unspooling terror of having to choose, without a map, who you might be next.

And yet we continue to idealise it. We curate the aesthetics of change like vintage records or coffee table books, Instagrammable transitions, phoenix-rising captions, wardrobe overhauls pretending to be psychological rebirths. We mistake renovation for revolution. Buying a one-way ticket to Tulum, rebranding in a Riads-and-rosewater chapter in Marrakech, doing ayahuasca in the Sacred Valley, the new haircut, the passive-aggressive captions about boundaries… all of it part of the elaborate masquerade that allows us to simulate change while keeping the underlying architecture of self exactly as it was: fragile, predictable, undisturbed. But the actual work, the breaking, the unbecoming, the long, unspectacular intervals where you are unsure if you are healing or just disassociating, that’s the part we keep off the record.

Are people capable of change? Yes, they are, but it’s inconvenient, uncomfortable, and wildly overrated if what you seek is comfort or coherence. To truly change is to step into cognitive dissonance so intense it gives you psychic blisters; to realise that your own defences, the ones that once protected you, are now the very bars of your self-imposed cage. Change, at its most honest, is the experience of reinhabiting your own body as if it were foreign. It doesn’t happen through books, though they help. It doesn’t happen through crisis, though it can catalyse it. It happens, more often than not, through long, lonely acts of attention, through a slow and steady series of decisions that contradict the reflexive logic of your former self.

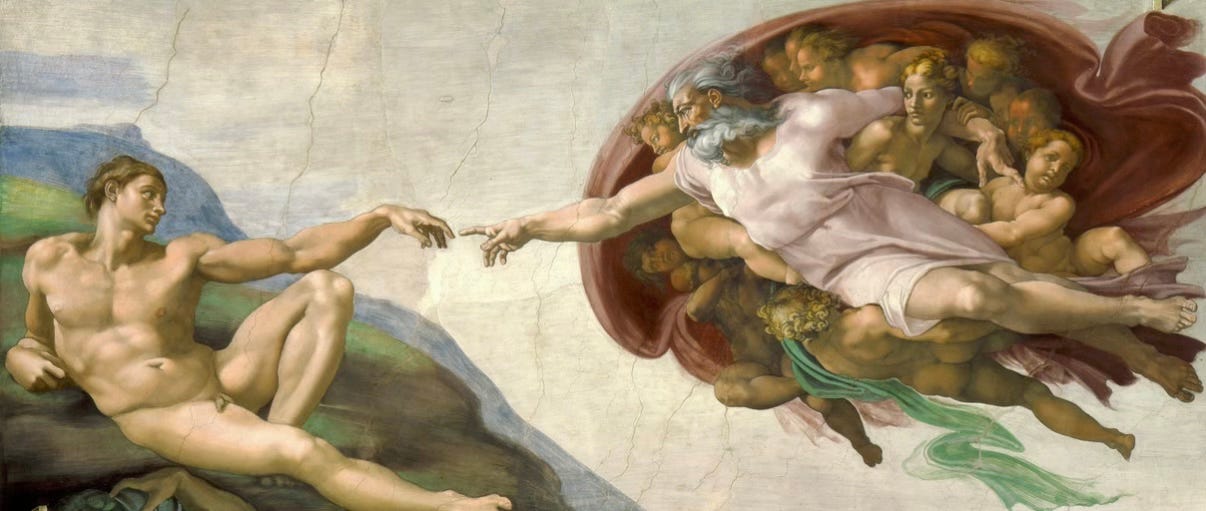

History, when read honestly, is a graveyard of change agents, both triumphant and tragic. From the tectonic shifts of Copernicus and Darwin, who dared to suggest that we are not, in fact, the center of the universe nor the final product of divine symmetry, to the quieter upheavals of women like Olympe de Gouges, who demanded equality during the French Revolution only to be executed for it, each instance of change is born out of intellectual heresy. Martin Luther nailed his thesis to the church door not as a branding exercise, but as a man possessed by the unbearable tension between inherited belief and observed truth. Change, historically, has always made people furious. Because it threatens not only what they believe, but who they are when they believe it.

The reason most people don’t change is not because they are incapable of doing so, but because the process requires a betrayal of self that feels like a form of death. It is psychologically expensive to examine your beliefs, your patterns, your loyalties, and admit that some of them were inherited without scrutiny. Many people would rather be consistent than free, rather be miserable in the known than risk joy in the unknown. They will keep playing the role life handed them in Act I, even when the audience has left and the theatre’s roof has caved in. And let’s not be gentle about it: some people simply lack the architecture for transformation. They are not broken or evil, they are, quite possibly, too hurt to try again. Change asks us to believe in possibility, but mostly in our own worthiness of it. Some people were never taught how.

When I was twenty-five, I had worked for three years in a job that made sense on paper – a good position with a nice salary, stability, professional promise. It was an elegant office with a boss who used the word “synergy” without irony. I remember watching myself from above: Tamara, dutiful, pleasant, efficient, dying. The days blurred, the projects multiplied, and my laughter, when it appeared, felt borrowed. One afternoon, I caught my own reflection in the elevator mirror and didn’t recognise the woman smoothing her blouse. She was playing someone else’s game. I quit with nothing lined up. No plan. Just the visceral certainty that I would rather risk drowning in my own voice than stay safe in someone else’s silence. That decision didn’t make me special. It made me desperate. But sometimes desperation is the most honest engine of change.

Culturally, we are taught to valorise change as long as it stays marketable. “Pivot” is the word used in tech, “rebrand” in media, “redefine yourself” in lifestyle magazines. But scratch the surface and you will see what we really want, which is novelty without consequence. The self-help industry, worth billions, is built on selling change as an accessory: here’s a morning routine, a mantra, a planner… now go fix your life in 21 days or less. Corporate culture, even when it preaches “disruption”, is pathologically allergic to true transformation. Why? Because transformation is messy, nonlinear, and impossible to spreadsheet. A genuinely transformed employee might question the system itself. That is insubordination, not innovation.

Technologically, we live under the illusion of perpetual evolution: apps update, phones upgrade, avatars get slicker. But this is not metamorphosis, it has become maintenance. These micro-adjustments give the impression of movement while keeping the user – us – cemented in the same behavioural loops. Our digital environments are algorithmically engineered to reward predictability. They do not want your complexity. They want your compliance. And so, the most drastic act of digital résistance might not be quitting the platform, but refusing to become a brand within it.

Politically, we only endorse change when it flatters our narrative. A man moves from conservative to liberal and we call it growth. He moves from liberal to conservative and we call it regression, or worse, betrayal. But real political change is rarely symmetrical. Malcolm X changed. Angela Davis changed. So did Winston Churchill – multiple times. But we remember these shifts only when they serve a myth of redemption. When they don’t, we discard them as inconsistency. Our obsession with ideological purity means that many people, especially in public life, are punished not for failing to change, but for daring to.

Then there is love, the crucible of all serious change. Not romantic love as sold to us by cinema and perfume ads, but the kind that rearranges your inner architecture. The love that demands you confront your patterns, your wounds, your inherited roles, and ask: who am I when I’m not being impressive? Who am I when I’m not being needed? Love that doesn’t soothe your trauma, but surfaces it. Love that is less about completion and more about exposure. I’ve had lovers who made me braver, and others who shrank me into my most polished version, charming, careful, palatable. The former left me raw but alive. The latter left me applauded but extinct.

Not everyone can change. And this is not cynicism, not at all, it is mercy. Some people cannot afford to. Some people do not want to. Some cling to their pain like an heirloom because it is the only thing that was ever truly theirs. Others mistake change for abandonment: of family, of culture, of self. There’s the woman who stays in the marriage because she was raised to believe endurance is virtue. There’s the man who refuses therapy because being broken is less terrifying than being reassembled. There are people for whom change would require confronting abuse, addiction, lies so tightly woven into their sense of self that pulling the thread might kill them. To say that anyone can change is cruel optimism. It turns trauma into a choice. It also erases the heroism of those who do.

Art, too, has always been a brutal rehearsal space for change, part prophecy, part autopsy. Real artists don’t simply reinvent their style for seasonal acclaim or gallery relevance; they rupture their own worldview, over and over, to excavate the next truth beneath the last performance. Picasso didn’t politely transition from Blue to Rose to Cubist, he devoured his own aesthetic certainties like a man possessed. Virginia Woolf, who began with Edwardian novels and ended by drowning herself, changed not for applause, but because her mind no longer fit the linguistic forms she had inherited. And what of Nina Simone, who mutated from a classically trained pianist into the feral voice of Black rage, not necessarily because she wanted to change, but because the silence around her left her no other ethical option? The real artistic metamorphosis is rarely palatable, rarely lucrative, and always spiritually expensive. It is the choice to burn the house of what once worked, to stand in the ashes of an old voice and wait, with nothing but dread and hunger, for a new one to arrive.

And what of generational change, the slow revolution that occurs in kitchens, in hushed conversations, in the refusal to inherit silence, not in headlines? I have seen daughters refuse to become their mothers, not because their mothers were wrong, but because survival looked different now. I have watched men raise sons without violence because they remember how it felt to flinch. And yet, intergenerational change is treacherous; it carries with it the risk of betrayal dressed as freedom. To change beyond your lineage is to risk being misunderstood by the very people whose love formed your first scaffolding. It is to break the familial pact that says: we suffer like this, in this shape, with these rituals. Sometimes, change is not becoming someone new but refusing to repeat who others were. It is a silent revolution that echoes across lifetimes, in the choice to speak when your grandmother stayed silent, to leave when your uncle endured, to heal in public when your father drank alone. And maybe that is the most radical kind of change: the one you make not only for yourself, but so the pain doesn’t metastasise down the line. So the story, if it must be told again, ends differently this time.

So if change is rare, unreliable, excruciating, why bother? Because it’s the only thing that allows life to be more than repetition. Because even the smallest acts of change, apologising without excuse, walking away from what you once begged for, seeing yourself without the mask, are the only real proofs of consciousness. We are not meant to remain fixed. We are not museums. We are scaffolds, always under construction.

And yet, let us not make a martyr out of change. It doesn’t always come bearing wisdom. Some changes are mistakes. Some are made too soon, or too late. Some are not changes at all, but regressions dressed as revelations. Change is not inherently good. It is simply inevitable. What matters is whether it is intentional. Whether it is metabolised. Whether it creates more life, more space, more breath. Or whether it simply rebrands the same wound in a different font.

If you are waiting for closure, you are still in the old paradigm. Change doesn’t conclude. It molts. It glitches. It returns. You will think you’ve evolved and then your mother calls and your voice reverts. You’ll believe you’ve healed until a familiar song plays and your bones betray you. There is no diploma in becoming. No certificate for being better. There is only the slow, embarrassing work of choosing to try again, differently, with no guarantee.

That, perhaps, is the final dignity: not that everyone changes, but that someone, against all evidence, against all conditioning, against the soft, lethal pull of staying the same – still chooses to. Someone gets out. Someone says no. Someone stops pretending. And in that moment, however quiet, however personal, the world shifts. Not for everyone. But for someone.

And sometimes, that someone is you.

From the wreckage of what no longer fits, I write, unfinished, with no illusions, no grand finale, only this: the quiet vow to change, again,

Tamara

Tamara, this is less a piece of writing and more a seismic act of truth-telling.

You dissected change, stripped it of its Instagram filters and TED Talk stage lights, and laid bare the raw, unglamorous marrow of transformation. Your prose walks a fine line between poetry and scalpel, wounding, necessary, and breathtaking in its precision.

What struck me most was how you refused to romanticize the process. The “psychic blisters,” the inherited roles, the unmarketable middle—these are the messy thresholds we all privately wrestle with, but rarely see reflected in writing that dares to be this honest. Your portrait of change isn’t linear or redemptive, it’s recursive, disorienting, and deeply human. And that refusal to offer closure? That’s where the courage lives.

The metaphor of “change as betrayal” hit me. We talk so much about empowerment, but rarely about the cost of evolution, especially when it means disappointing the systems, beliefs, and people that once defined us. And the revolution of generational change? That part gave me chills. The way you described the daughter refusing inherited pain or the man choosing not to raise his hand, that is something else. Only you can write like this.

Here’s what I keep turning over in my mind though, if we accept that not everyone can—or should—change, how do we hold compassion for those still caught in their inherited scripts, without being dragged back into them ourselves? How do we metabolize empathy without martyring our own becoming?

Thank you, Tamara, for writing from the wreckage. It’s a rare thing to feel seen and called forward in the same breath.

You've articulated something here that I rarely see explained well: individuals vary in their capacity to change, in accordance to some specific arbitrary goal imposed on the self, but everyone is simultaneously an agent of change insofar as our actions change the world around us, even in the most miniscule, undetectable ways.

The generational rebellion is the natural cause-and-effect of people vowing to do things differently than their parents, regardless of what their parents actually did; the change from conservative to liberal or from godless heathen to believer is seen as progress, simply because it's a RESPONSE. Evolution is actually a process of causal extinction, as the old makes way for the new and the disgruntled seek recompense.

As you state, real change is, in essence a violent reactivity, not for moral grandstanding or ceremonial sacrifice, but out of necessity; of desperation. It's as morally and ethically neutral as it is inevitable, and even arbitrary. What changes is the perception or illusion of control; the performative aspects all in support of a belief that we can make our lives better if we just do x,y,z, and the incentive to commodify and, to make up a word, "cultify" those hopes.

Thank you, as always, for oiling the gears between my ears. Your ability to deliver remains unchanged.